An Ingenious, Unscrupulous, and Offensive Advertiser

During America's Gilded Age, a wealthy man named John Wanamaker finds his way into the presidential cabinet - and sees an opportunity to grow his business

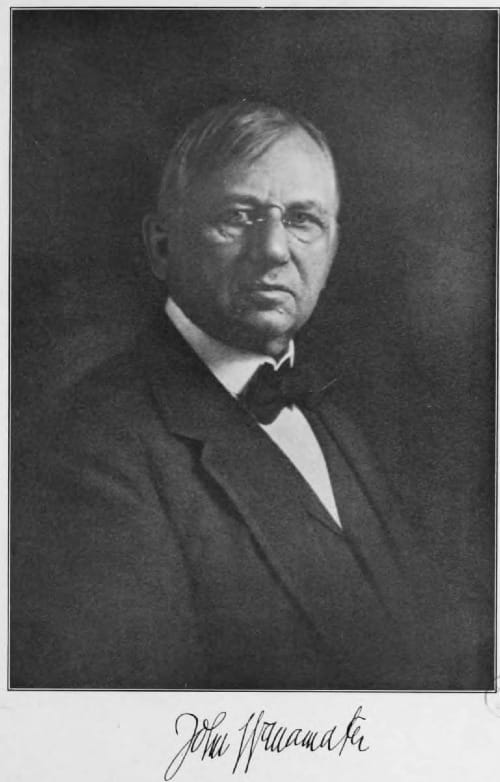

John Wanamaker was a 19th century Philadelphia retail magnate who founded Wanamaker's department store, the largest retail store in America at the time. He also used his immense wealth and political connections to secure a role in the presidential cabinet as Postmaster General.

Although he's remembered for his innovations in retail and marketing, Wanamaker faced several controversies during his time at the Post Office Department. He sought to expand postal service in the United States in an effort to grow his own department store business, attempted to recruit his postal employees as sales agents, and banned books as punishment for his personal business dealings.

Listen to our latest episode on Spotify and please give us a follow!

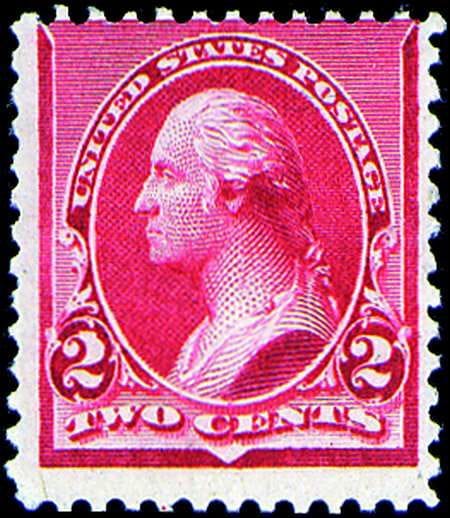

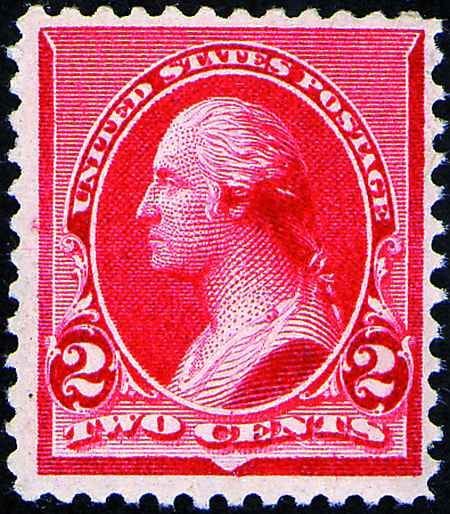

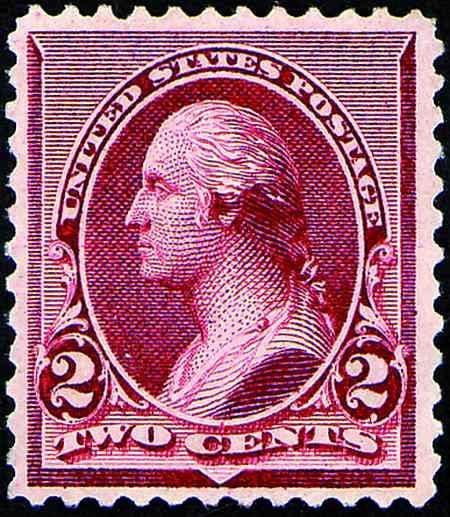

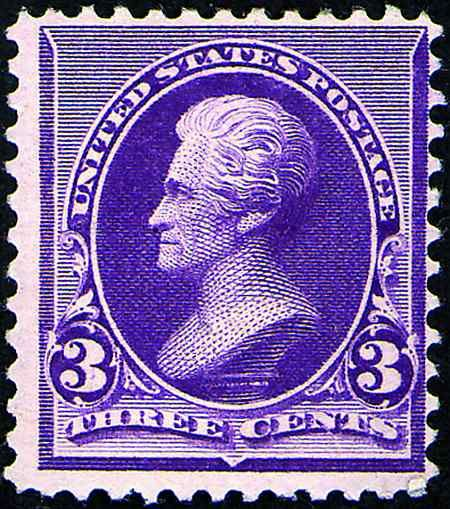

John Wanamaker's stamps:

The many shades of the 2¢ Washington stamps (source)

Sources

- Wanamaker's piracy - https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1890/05/29/103245368.html?pageNumber=4

- Tariff court cases - https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1891/11/07/103349048.html?pageNumber=4

- Ugly stamps - https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1890/03/03/103231804.html?pageNumber=8

- Postmasters as sales agents - https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1889/04/19/106345882.html?pageNumber=4

- Presidential campaign funds - https://www.nytimes.com/1932/08/28/archives/presidential-campaign-funds-have-varied-with-the-years.html

- Blocks of Five scandal - https://www.itakehistory.com/post/blocks-of-five

- Tolstoy ban - https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1890/08/01/103255518.html?pageNumber=4

https://www.newspapers.com/image/86435031/?match=1&terms=wanamaker kreutzer discount - Original Edison recording (unenhanced) - https://archive.org/details/EDIS-SRP-0190-03

Episode Transcript

Cameron: The year is 1888 and the US presidential race is in full swing between Democratic incumbent Grover Cleveland and his Republican opponent, Benjamin Harrison. But as November approaches, it's becoming clear to the Harrison campaign that they simply don't have the numbers to win. Luckily for them, one of the wealthiest businessmen in America is more than happy to help. But in return, he wants a position in the President's cabinet. And not just any role. He wants the job of Postmaster General. John Wanamaker, the founder of Wanamaker's Department store, was a retail innovator who bought his way into the world of politics. His investment in the Harrison campaign earned him immense political power, which he used in ways that were both groundbreaking and incredibly scandalous.

Today on Lost Threads, we're exploring John Wanamaker's controversial legacy as a wealthy businessman turned Postmaster General. I'm Cameron Ezell.

Cory: And I'm Cory Munson. We'll be right back.

Cory: Before he was Postmaster General, John Wanamaker was a humble shopkeeper, and by humble, I mean he owned one of the largest department stores in the United States.

Wanamaker was born and raised, and died, in Philadelphia. He was in the retail game from an early age. In his early twenties, he and his brother-in-law opened a men's clothing store called, Oak Hall.

Cameron: Great name for a clothing store.

Cory: It was also successful. A decade later, he'd saved up enough cash to buy an enormous abandoned train depot, which he renamed Wanamakers. This was one of the first department stores in the United States and eventually it was the largest retail store in America.

Before this era, basically everything was a specialty store. So if you went out and you needed to buy a tie and pantyhose and stationary you were going to three stores.

Cameron: yeah. And shoppers at those stores were chaperoned during their entire visit by a salesperson. You didn't really idly browse. You were shown requested goods and either purchased them or made a custom order, and then when you made the purchase you were expected to leave.

Cory: I guess the, closest comparison today would be something like a fancy boutique clothing store.

Cameron: But after this, department stores started popping up in big cities. And suddenly the entire shopping culture is turned on its head. People could go into one building to browse or buy practically anything they wanted.

Cory: And one, of the reasons Wanamaker is so famous is because he pioneered a lot of this. That includes standardizing the price tag.

Cameron: Yeah. Before this era, goods didn't really have set prices. Customers were pretty much expected to haggle.

Cory: That sounds exhausting.

Cameron: And Wanamaker's reasoning for implementing price tags is interesting. He was a deeply religious man and he believed that all men are equal in the eyes of God. So it wasn't ethical to upcharge someone just because they could afford it.

Cory: Another thing he did at his store was turn it into kind of a community gathering third place.

Cameron: Yeah, I remember reading about the giant eagle statue in the store, and a phrase among locals at the time was to meet at the eagle.

Cory: It was a hangout place, like a mall today. He kept his store open until 10:30 PM but you couldn't buy anything after 7:30, so it was just open for people to hang out, browse, check out architecture, eat at the in-store restaurant.

Cameron: It's hard to imagine a store staying open for three hours after cash registers closed. And since it's a department store, I imagine it had a lot more to offer.

Cory: Yeah, like all the modern high tech that he had in the store. Wanamaker was obsessed with bringing bleeding edge technology into the shopping experience. This was an era when a ton of things were being invented, and if you wanted to see them, all you had to do was go into his store.

Cameron: Yeah, totally. There was electric lights, telephones, pneumatic tubes, elevators, and all of those were added to his store basically as soon as they were invented.

Cory: No matter how great your store is, you're not gonna sell anything until you can get people through the doors.

Cameron: Yeah. He was a marketing pioneer. One of the things that brought Wanamaker to my attention is a quote of his I saw in a PowerPoint presentation: "half the money I spend on advertising is wasted. The trouble is, I don't know which half."

Cory: So he's saying that marketers have a general sense that they're overspending on their advertising. Like it's impossible to know where to spend money. So you kind of just need to flood the zone.

Cameron: Marketing companies aren't entirely sure about how efficiently they're spending their budget, and that's why everything these days is about gathering as much consumer data as possible to get way better insight on what you're wasting.

The quote shows that even in the late 1800s, Wanamaker understood where marketing was starting to evolve.

Cory: I bet he would've loved targeted advertising.

Cameron: One of his lasting legacies is what's referred to as Wanamaker style advertising, which really doesn't give enough credit to the man behind the strategy: John Emory Powers. Powers was considered one of the world's first full-time copywriters and he took a direct and honest approach to his work, which was a great fit to how Wanamaker approached retail. Powers was quoted as saying, " print the news of the store. No catchy headings, no smartness, no brag, no fine writing, no fooling, no attempt at advertising, no anxiety to sell, no mercenary admiration. Hang up the goods in the papers, one at a time. A few today, tomorrow the same, or others."

Cory: We do a lot of newspaper research, you know, through like old archives and, we run into the pre-Wanamaker style of ads all the time. Everything that's for sale is amazing and a miracle cure, and it'll solve all of your problems. Today we would call those ads hyperbolic at best and untruths at worst. Can you give an example of what one of Wanamaker's newfangled, honest ads would've looked like?

Cameron: Well, let's look at an advertisement before Wanamaker hired Powers. This one is pretty much boilerplate for the era focusing on exceptional quality.

So the copy reads "unusual prices for very fine black silks. The quality cannot be duplicated again, except at considerable advance. Handsome silk."

Post-Powers, You've got ones that say things like "soiled pieces of muslin underwear at two thirds price today. Soiled, but otherwise uninjured. It will go quickly.

Cory: I hope soiled meant something different back then.

Cameron: Yeah, I'm hoping these aren't used Muslin underwear.

One more. If you show it to us and give a bad account of how it was worn, we will send you away content somehow. Can't tell how. Don't know how, but we shall find out.

Cory: You know, I can see how that would resonate with people. They're worded like you're talking to just some matter of fact, employee who's kind of tired of his job and wants to give you the backroom deal.

Cameron: And another thing to mention is how heavily their ads promote returns and the ability to get your money back if you're not happy.

That was actually new, and I have to imagine it generated a ton of goodwill with the company.

Cory: So it sounded like being brutally honest and casual worked for Wanamakers.

Cameron: Oh yeah. It was incredibly successful. In the first few years after Powers took the job, the store's sales volume doubled from $4 million to 8 million.

Cory: You know, we're calling this type of ad copy innovative, but it doesn't really seem like marketers follow this example today. Today ads are all about how this is a great product that will change your life. McDonald's isn't doing a campaign with a tagline. We're not the best, but our food is cheap and it fills you up.

Cameron: I mean it, it's important to know that like marketing techniques come and go as consumers get used to certain styles and after a while we just start to tune them out. So take banner ads for example. When was the last time you actually clicked a banner ad?

Cory: Well, sometimes for my day job, I have to test them out, but outside of that, I don't know, maybe a decade.

Cameron: I maybe click them by mistake sometimes. But they actually used to be a very effective method since they were just a brand new idea. The very first banner ad had a click-through rate of 44%. Today, a good click-through rate on banner display ads is half a percent. Another example I can think about is that a few years back, Domino's had this ad campaign about how their pizza actually sucked. So they changed the recipe and that seems very Wanamaker style to me.

Cory: So shoppers loved Wanamakers for all the reasons we've talked about. It was futuristic. It had everything you needed in one place, money back guarantees, honest advertising. But I would argue that none of those were the most important reason for why the store was so popular.

At the end of the day, Wanamakers was simply incredibly affordable. And that's because they developed a lot of the retail cost saving strategies that companies use today. For example, Wanamakers focused on sales volume over profit margin.

By purchasing goods in large quantities, they could get better bulk discounts from the distributors. This then allowed them to sell the goods for cheaper, which undercut the competition and brought in more customers.

Additionally, Wanamaker's used a tactic known as white labeling. Instead of purchasing brand name products for resale, his store would buy things like coats, sewing machines, mattresses directly from the factory, and then just attach the Wanamaker brand.

Cameron: So basically they were making the 19th century version of Kirkland Signature or Great Value.

Cory: Exactly.

Cameron: So these are all the markers of a highly successful business, but we're not seeing Wanamaker stores in every city today. So I'm sure there's a reason it hasn't stuck around.

Cory: Yeah. Wanamaker had one major flaw, which was that he did not want to share any decision making power or let anyone else manage his store

Cameron: And they only had the one store in Philadelphia, right?

Cory: For a long time. Yeah. They did eventually open one up in New York, but that wasn't until 1896, so a decade after this story. And it does feel like a missed opportunity that they didn't branch out. Their model was light years ahead of any local competition. Like they could have been what Macy's or JC Penney's is today, but Wanamaker had to be at the helm and that meant his retail empire's growth was limited.

And it's this iron grip over his business that actually brings us into our next section. He wasn't able to expand, but he could still consolidate his regional power. And the best way to do that was to follow a model that many in the American elite were already exploiting during the Gilded Age. John Wanamaker was about to enter politics, and lucky for him, the 1888 presidential election was right around the corner.

During the 1888 campaign season, the Democrats and Republicans supported two opposing economic policies. Democrats wanted reduced tariffs, which among other things would increase global trade. Republicans on the other hand, were in favor of increasing tariffs, believing they would help protect American manufacturers.

Cameron: Wow. A whole campaign centered around tariffs.

Cory: Back then, tariffs were actually a little bit more important. There was no federal income tax, so most of the government's funding came from tariffs.

If they were reduced, like how the Democrats wanted, the government would have to make up that deficit by increasing taxes, particularly for large businesses and the wealthy.

Wanamaker was a wealthy business owner. He purchased many of his goods through American manufacturers and suppliers, so he felt like tariffs were a good idea. Since the Republicans were the ones pushing those America first protectionist policies, he threw his support behind their nominee: Benjamin Harrison.

Wanamaker donated $10,000 to the Harrison campaign and convinced other Philadelphia business owners to do the same. Overall, he helped raise $400,000 or around $13 million when adjusted for inflation.

Cameron: Okay. Maybe I'm just jaded by the current state of politics in the US, but 13 million sounds kind of puny today. Back during the 2024 election, Kamala Harris raised over a billion.

Cory: That 400,000 was pretty substantial at the time. In the previous presidential election, Grover Cleveland's total campaign fund was about 1.4 million. His opponent, James Blaine had only a hundred thousand dollars in his war chest.

Cameron: So Wanamaker's fundraising would've been like a third of the previous President's entire campaign. Wanamaker wants to bolster the pro tariff candidate, but he's putting in a lot of work. Is there something else here he's hoping for besides a business friendly White House?

Cory: You are right to be suspicious. Wanamaker had big plans if the Republicans won the White House. More than anything, he wanted to be appointed Postmaster general.

Cameron: That seems like such a weird position for a guy like Wanamaker to pursue.

Cory: Yeah. It's not the most illustrious appointment today, but at the time, this was a very powerful position and it would've really helped him expand his business empire.

Cameron: Why would that help to build his business more?

Cory: First of all, the mail was a huge part of everyone's lives.

There were telegraphs for advanced communication, but the postal service was the main way people talked to each other. The postmaster general had significant sway over the media, which we'll get into later. Also, back then, the postmaster General wasn't just head of the post office, they were on the presidential cabinet, which hasn't been the case since the 1970s. Being in the cabinet meant private time with the president, which means influence.

So back to the 1888 campaign: although the Republicans were well funded, their platform lacked popular support. Most Americans in the late 19th century did not believe increasing tariffs was effective economic policy. Facing a clear disadvantage in winning the popular vote, Republicans focused their efforts on winning the electoral college.

The key state in the 1888 election was Indiana, Harrison's home state. Unfortunately, it seemed like his campaign there was doomed. They were trailing in a state that should have been a shoe-in. But they had a final last ditch plan to swing the vote their way. In the fall of 1888, the treasurer of the Indiana Republican Party drafted a letter to state leaders telling them to focus their funds on hiring "floaters", which was the name for voters who were up for hire. If the Republicans paid them enough, they'd vote Republican.

Cameron: Okay, so the Republicans are gonna pay people to vote their way in the election. Sounds illegal, but let's ignore that. Say I'm a floater. The Republicans pay me to vote for their candidate. Couldn't I just take their money and vote for whoever? It's not like they would know.

Cory: Today, we have a lot of privacy in the voting booth. Maybe too much.

Cameron: Why would you say that?

Cory: But secret ballots weren't introduced until after this. In this election, and in the ones before, the way it worked is that you would walk up to the voting place and ask for a specific party ticket. You'd be like, I'd like to vote for the Democrats. And they'd hand you a blue color ticket that told the whole room which way you were voting.

Cameron: So if the person paying me was at the polling location, they would definitely know who I voted for.

Cory: Yeah. And by the way, according to this scheme, I don't think they've paid you yet. They're going to wait to make sure you've done the job correctly. That's why the secret letter urged floaters to vote in groups of five or blocks of five, as the scandal came to be called.

Each block was led by a trusted party man who would hold everyone accountable and then report to the bosses, and then you'd get paid. Eventually, the Republican letter was leaked and there was plenty of public outrage. Earlier you said, this sounds illegal. Yeah, it absolutely was. And the Indiana Republican leaders went on the defense calling the letter a forgery and threatening libel suits.

Cameron: And I'm sure just like the Democrats today, they stood up and held them accountable.

Cory: No. The Democrats backed down and although the letter leaked, the strategy still worked. Harrison won his home state of Indiana. He lost the popular vote by less than 1%, but they were expecting that. He won the electoral college 233 to 168.

Cameron: Okay, so Harrison won and Wanamaker's $10,000 investment paid off.

Cory: Absolutely. He got everything he wanted. A month after Harrison was sworn into office as the 23rd president, John Wanamaker was confirmed as the United States Postmaster General.

Cameron: And this doesn't seem all that scandalous today, right? Because we see wealthy donors end up in the federal government all the time. Even Trump appointed a rich businessman and one of his big donors to Postmaster during his first term, and that guy had direct conflicts of interest.

Cory: Yeah. But high level positions for wealthy donors were definitely not common back then. I think we've just become accustomed to it. There was a lot of public outrage and criticism regarding Wanamaker's appointment to the cabinet.

Cameron: I liked this quote, which the New York Times said about John Wanamaker right after he was appointed. He is an ingenious, unscrupulous, and offensive advertiser, and he looks upon all human events as creating or as failing to create opportunities whereby more people may be made to buy more goods at his store.

Cory: And that quote perfectly foreshadows the next section. Wanamaker finally got the cabinet position he wanted, and he immediately started pushing for radical changes to the postal service.

But there were a lot of questions about his motivations for all of these changes. And while they were popular with the public, it seemed like every reform had one thing in common: they were also good for John Wanamaker.

Cameron: Just as he had reinvented the American shopping experience, Wanamaker as Postmaster General wanted to reshape the postal service in ways that would extend far beyond simple mail delivery. Now, remember that Wanamaker was an innovator. This is the guy that popularized price tags and the money back guarantee.

From day one, he had plenty of ideas for services that would benefit the public. A great example of this was postal banking.

Wanamaker's idea was to provide Americans with basic financial services through their local post office.

Cory: I really like the idea of using postal offices as banks. I know countries like Japan do it and they're super popular.

Cameron: it also came out of his personal experience. Money management was really important to Wanamaker and in fact, the year before he was appointed, he created a penny savings bank at a Sunday school to encourage young people to start saving money.

Cory: Good for him. I can't help but notice we don't have postal banks nowadays.

Cameron: Yeah, Wanamaker was a little ahead of his time. President Harrison thought the idea was too socialist. Postal banking was eventually introduced in 1911 before it closed in 1967.

Cory: Why did it close in 1967?

Cameron: People at the top thought banking was something the private sector should do, and they called it obsolete, which is a shame because it was still popular with everyday people. It didn't issue loans or anything, but it was a safe and convenient place to keep your money.

Cory: Now people who struggle accessing banks get to put their money in Venmo.

Cameron: Which it really isn't the best place to keep it because it's not insured by the government. It's pretty unsafe. So postal banking didn't work out, but other Wanamaker ideas would later become staples of the postal service. Though at the time they were highly controversial, especially given the man who is promoting them.

The main two worth discussing are rural free delivery and parcel post. So surprisingly up until this time, the postal service had never been in the business of delivering packages. Historically, it had a very simple but important function: facilitate communication between people. Which pretty much meant delivering letters and periodicals.

If you wanted a parcel delivered to your doorstep, you'd need to go through a private courier company. But Wanamaker envisioned a future where the federal government was also in the business of delivering commercial packages.

Cory: That's actually a huge change, right? Because he's arguing that the entire post office machine should shift from helping citizens communicate to delivering products on behalf of companies.

Cameron: Yeah, and look who's trying to implement this policy: a rich business owner who owns a department store. Pretty convenient! Critics saw this as an opportunity for Wanamaker to make more money; let people order his goods through the mail, and the taxpayers can subsidize the couriers. But it's also important to note that it was a popular idea.

People were already ordering from the Sears catalog at this point, but they'd have to pick up their goods from the nearest train station on their own and usually get it delivered to their house through a private courier.

Cory: Yeah. Parcel delivery sounds like it would be very popular, especially for people who lived in rural areas and couldn't, you know, make a quick trip to those huge department stores.

Cameron: Exactly. And back then, if you lived in the countryside, not only were you not getting packages delivered to your home, you also weren't getting letters.

Cory: Rural Americans didn't get mail delivery?

Cameron: Up until the late 19th century, if you lived on a farm or in the country, you had to make the trip into town to pick up the mail. And remember, this is before the automobile, so that meant a trip that could take all day just to receive correspondence and newspapers or you know, any information about the outside world.

Cory: That sounds pretty isolating.

Cameron: It was, especially in the late 1800s when the world was starting to change pretty fast. So rural delivery became something of a pet project for Wanamaker. To him, it made sense that Americans living in the country should get the same access to information and goods as everyone else.

And like I mentioned before, opponents called out the obvious conflict of interest, saying rural delivery meant a lot more people could have Wanamaker products delivered right to their doorstep.

Cory: We have rural delivery and parcel post today, so it seems like he was able to get these changes pushed through, right?

Cameron: Unfortunately, for Wanamaker, rural delivery and parcel post wouldn't get passed during this term. They weren't seen as worth the cost at the time. And private express companies had a bunch of congressional allies and they would not let parcel posts catch on. One of Wanamaker's biggest critics was Senator Thomas Platt from New York.

And although Platt said he was concerned about Wanamaker profiting, he just so happened to be the director of the United States Express Company, which was a private parcel and freight service.

Cory: So they didn't get passed during his term. How long did it take for them to become standard practice?

Cameron: It took a few decades. Parcel posts and rural delivery wouldn't begin until the early 1900s. And by the way, Congress continued to fail to see the value in both of them. The only reason we got those services is because small towns started demanding them.

Cory: Okay, Cameron, I'm hearing a lot about what Wanamaker didn't do. What did this man get accomplished while he was in office?

Cameron: Not much that puts him in a great light. There was a lot of truth to what those critics were saying. He would've absolutely benefited from rural delivery and parcel post. One of the interesting things about Wanamaker is that he was a progressive and innovative guy, but in doing a lot of research about him, I think a lot of his legacy has been whitewashed to highlight his modern altruistic qualities. Based on a few Google searches and what the USPS has on their website, you would think that Wanamaker was a savvy businessman who successfully brought his experience at the department store to the postal service. But if you dig in a bit more, it's pretty clear he wasn't well-liked at the time. He was constantly under fire for some new scandal, an abuse of power, or coming up with some scheme that would make him wealthier.

Cory: As someone who has also spent a lot of time researching him, I can attest that he enjoys a pretty squeaky clean reputation today. I don't think we're here to say "wake up people, this guy actually really sucked", but there is an interesting story here about an incredibly rich person who found himself in a position of power in an era when a lot of the stuff that's illegal today was new territory. And he pushed a lot of boundaries to enrich himself.

Cameron: Exactly. A good example of that is this story we found about when the ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica was released. Wanamaker, while he was postmaster general, decided to pirate the book and make photographic copies of each page so he could produce his own cheaper version to sell at his store.

Cory: It's kind of crazy, but back then, the US had essentially zero copyright laws for foreign publications.

What he was doing wasn't necessarily illegal, but people knew that it wasn't right. The New York Times pretty much called him a pirate and a cheat.

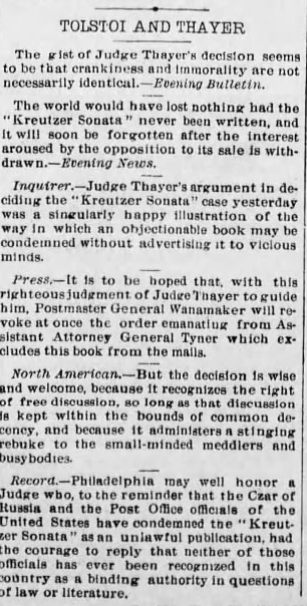

Cameron: And another really good example of this was the whole Kreutzer Sonata incident.

Cory: Oh God. Yeah. That was a bad one. Can you set that one up real quick?

Cameron: Sure. So when Wanamaker was in office, Tolstoy had just finished a novel called the Kreutzer Sonata. The publisher sent out this early order discount to Wanamaker's department store, however, they decided not to buy any.

But then it turned out that Kreutzer Sonata was a smash hit, and Wanamaker was like, we should definitely have bought the book when it was being discounted.

So, he contacts the publisher, tells them they would like to place a large order with the pre-release discount. The publisher was like, the book's already out. So no, we're not doing the early bird discount. Wanamaker says, unless he gets the early discount, he's not going to carry the book in his store at all.

Cory: And spoiler, he doesn't end up carrying the book. But when asked by the press, he said it had nothing to do with not getting the discount. He said that the quality of the book was below the store's standards, so they wouldn't disgrace their shelves by selling it.

Cameron: And you would think the story would just end there, right? Like he's just not going to buy the book, but he's the postmaster general now, so later that month, he forbids the delivery of the Kreutzer Sonata through the US Mail.

Cory: And this is why the Postmaster General was such a powerful position back then. The way he was able to ban the book is really interesting.

Cameron: Yeah. What happens is the US Attorney General receives a complaint from someone in the public that the book is indecent. The AG reads it and agrees, and according to the Comstock Act, which had just passed a decade before, the government had the right to prevent the distribution of obscene, lewd, or lascivious material.

Cory: That doesn't technically ban the book, right? But now it can't be sent through the mail, so it might as well be banned.

Cameron: Yeah. I mean if you can't ship the book, it's really hard to distribute and it's a pretty cunning move on his part. Wanamaker's able to punish the publisher while at the same time saying, look, someone submitted a complaint, I'm just following the law.

Cory: So why did people find the book objectionable anyway?

Cameron: God, it, it was a disgusting book. It actually went as far as criticizing the institution of marriage.

Cory: You know, the crazy thing is that the Comstock Act is still around.

Cameron: Yeah. It's still used today to try and ban all sorts of things from birth control to pornography, and for the most part, state and local laws have given consumers a lot more protections that supersede the federal law, but it's still technically on the books.

Cory: The funny thing about this story is that there's a little bit of a Jimmy Kimmel effect here.

Cameron: Right. That the ban ended up making the book more popular.

Cory: Yeah. Because the ban under the Comstock Act eventually gets overturned, and then all the press coverage creates a spike in demand, and the publisher immediately sets out creating a second edition.

Cameron: Real quick, I wanted to read a quote from the judge in that case.

" The Czar of Russia and the post office officials of the United States have condemned this book as an unlawful publication. Without disparaging the respect due to these high officials, I can only say that neither has ever been recognized as a binding authority in questions of either law or literature."

Cory: Comparing Russian principles to American government policy was just as damning back then as it is today.

Only a month after Wanamaker took office, Postmasters across the country, received letters calling on them to act as quote: "sales agents for the largest clothing and merchant tailoring business in the United States". The letters were sent out on Wanamaker's department store letterhead.

Once word got out, Wanamaker denied that he personally sent this letter. However, he also clarified that it was a legitimate and proper means for pushing trade.

Cameron: That is wild and pretty brazen. And it also feels like we see some of this today where people like Elon Musk get involved in the government and suddenly there's government contracts to use his AI models.

Cory: Yeah, again, this is something we're all kind of numb to now, but this was a huge scandal. Wanamaker was basically asking his federal employees to pick up a side hustle for his department store. And it was kind of like a pyramid scheme because he said, if you are not interested, then you should provide the names of two other people who might be. Obviously after the letter was made public, the whole scheme was shut down. But the point here is that he tried. He had no problem sending a letter out just to see what would happen before backing down after he met resistance.

Cameron: Hey, I mean, people don't get rich by leaving opportunities on the table.

Cory: And we haven't even talked about the tariffs yet. As soon as he got into office, Harrison made good on all those high tariff, America first policies that he ran on. In 1890, he signed a comprehensive Tariff Act, championed by fellow Republican representative William McKinley.

This law, better known as the McKinley Tariff Act, significantly raised rates on pretty much all foreign manufactured imports. Like any tariff, the goal was to promote national production, but in reality, everything just got more expensive.

Cameron: Hey Cory, just asking for a friend, but how did those high tariffs work out?

Cory: Well, Cameron's friend, the nation slid into a depression. Wanamaker, who remember, originally entered office to better position his department store, soon found that tariffs were affecting his bottom line, and he was forced to go on the defensive. On behalf of his department store, he was able to bring a large number of lawsuits against the US government directly to the Supreme Court.

Cameron: So while he's employed by the US government, he's suing them and for tariffs that he wanted in the first place.

Cory: Yeah, that's basically what happened. In these suits, his lawyers argued that certain goods, which Wanamaker's either imported or relied on, should be reclassified in order to lower their duty costs.

Cameron: What kind of stuff was he trying to argue for to be recategorized?

Cory: So before all of this, silk ribbons were classified as a commodity in the category of silk.

Cameron: Yeah, that makes sense.

Cory: But Wanamaker's lawyers argued that they should be reclassified in the category of hat material. That's because silk carried a significant tariff of 50%, but hat material was only 20%. The result, obviously, is that he can keep prices lower at his store. And yes, Wanamaker ended up winning that case and many others like it.

Cameron: Does this mean that Wanamaker started to change his mind on the tariff policy?

Cory: No. Publicly, he was still promoting the administration's tariff policy. In fact, with respect to the bill, he's quoted as saying, " I think it is not high enough to properly build up home industries."

Cameron: I mean, the public had to have seen through the hypocrisy of him getting favorable rulings for things related to his business.

Cory: Absolutely. But if you asked him, he said that his lawsuits were less about the tariff rates and more about just the due diligence of putting goods in their proper categories. The New York Times questioned Wanamaker's stance, obviously, saying quote, "and why should Mr. Wanamaker ever complain that the duties assessed on his imported goods are higher if these duties are to be paid by the foreign manufacturer?"

Cameron: It's a great point.

During the campaign, Harrison really worked hard to convince the public that tariffs would make America stronger and other countries would pay the costs. But instead what happened is small businesses had to pick up the tab, and unlike Wanamaker, they couldn't get in front of the Supreme Court whenever they wanted a good reclassified.

There's a reason the tariffs didn't last beyond this administration, and all I can say is that history has not been kind to Harrison.

Cory: Yeah. He was a one term president and he lost the next election to his former rival Grover Cleveland. And by this time people were sick of all that gilded Age stuff. Within a decade, the pendulum would swing pretty hard towards economic populism and anti-corruption under Teddy Roosevelt.

Anyway, since we're here, why don't we wrap up the story? What happened to Wanamaker after all this? Did he stay in politics?

Cameron: Well after Harrison's term ended, he went back to enjoy his private life at his department store.

Cory: I'd argue that he never really left.

Cameron: He did later try running as a senator and then governor, but neither worked out. He pretty much worked until the day he died at the age of 84, and that was in 1922.

Cory: And for all his hard work, we don't even have a Wanamaker's today.

Cameron: Unfortunately, no, but it did last a while. Macy's bought the store in 1995 where it was at its original Grand Depot location and that stayed in business until 2025.

Cory: I'm curious, what are your final thoughts on, uh, John Wanamaker?

Cameron: It's tough because there's two sides to him. Like we said, he has a pretty rosy reputation today for what he did in retail and marketing. And despite some of those motivations he had around self enrichment, some of his ideas as a postmaster were good policy even if they never did get past the drawing board.

So, parcel post, rural delivery, postal banking- those happened over the next few decades.

Cory: I mean, speaking of motivations, his major goal was to turn the post office into a business service, and that's absolutely happened. In 2024, The USPS brought in 60% of its revenue from marketing mail and parcel post alone.

Cameron: yeah, it's definitely more of an enterprise service these days than it is for consumers. I mean, we still use it, but yeah, that's a lot of revenue just from business services.

Cory: The big thing I took from this episode is probably something that I believed before this, but doing all the research here solidified the idea that maybe people who are good at running businesses don't necessarily need to have high seats in government. To me, those skills could translate well, but they're certainly not the most important skill to have in public service. I think it's valuable to have a background in law or in running a small town, a school, a library, anything before you enter the public sector and start making really big decisions for people. Just because you're good at making money doesn't mean you're good at government administration.

Cameron: Yeah, and people sort of idolize business owners and see it as like a really highly valued trait for politicians today. I went to the White House website the other day to look at Trump's cabinet, and most of them are not career public servants or attorneys.

There is a few, but for the most part it's former businessmen and women. You've got TV show hosts, venture capitalists, reality TV stars, athletes, a few CEOs.

Cory: And someone who is in charge of the WWE.

Cameron: I mean, that could be useful. Who knows?

Before we close out this episode, there's a few things that came up in our research that I thought were pretty interesting. In 190 8, 20 years after he was postmaster, John Wanamaker got sick and he wasn't able to attend the annual gathering of the Pennsylvania German Society. As president of the organization, he made a recording of a Leo Tolstoy anecdote on a brand new technology, the Edison phonograph, so that he could deliver an introduction to the meeting.

Cory: Oh, interesting. The very same Leo Tolstoy whose book he tried to ban..

Cameron: Yep. The original Edison recording's a bit rough and difficult to understand. So we did use some AI to help enhance the audio. Forgive us.

(Wanamaker recording: That fine, old Russian philosopher [Tolstoy] was once passing along the roadside, when he stopped to watch a man that was plowing. And calling over the fence to him, asked him to stop for a moment's conversation. When he said "my friend, what would you do if you were sure that you would die tomorrow? What would you do today?" He said "I would keep on plowing." The voice of the honorable John Wanamaker. November 5th, 1908.)

Cory: It is pretty crazy that we can hear the voice of someone who's born in 1838.

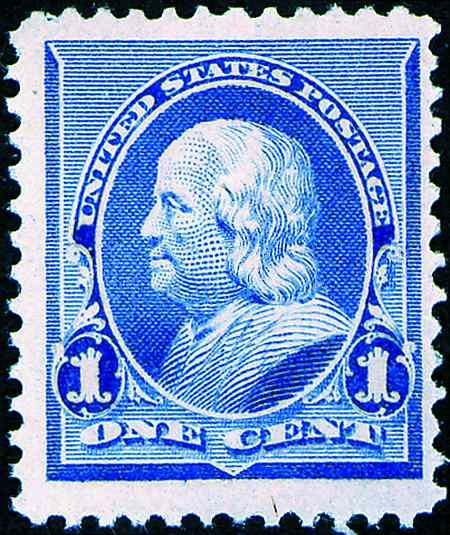

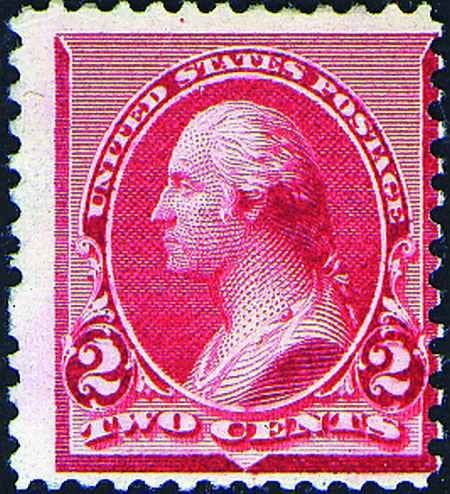

Cameron: The last thing I wanted to show you, Cory, are some of the stamps that John Wanamaker released while he was postmaster, because here's what the New York Times wrote at the time, quote. " The most recent product of John Wanamaker's, management of the post office department is the new series of postage stamps, which are decidedly the ugliest that this country has yet experienced."

So it may be a while since you've seen one of these, I, I sent you a link here, or can you look at this link.

Go ahead and describe this Benjamin Franklin, if you would.

Cory: Well, it's called 1891 C Franklin Dull Blue. And Franklin does look a little dull in this one. He's kind of, uh, he has a very flat profile. His forehead is about as straight as his chin. He looks, I don't know, bummed out.

Cameron: His eyes are just like vacant. He kind of looks like an old woman. He's got that neck waddle.

Cory: I think it's disappointment is the reaction is the look I'm seeing in his face.

Cameron: The Times said it ended up making him resemble the putty faced personification of senility.

He looks like somebody who did just try escaping the nursing home.

Cory: it looks like it's a nursing home mugshot.

Cameron: Members of the American Philatelic Society at the time said quote: "this is the worst series ever issued, both in regard to execution and material. The stamps are a disgrace to the country."

Cory: Well anyway, if you wanna check out these godawful stamps, you can find them on our website at lostthreads.org. That's where you'll also find links to the visual elements and sources for this episode.

If you liked today's show and want to continue to support us, please give us a follow on Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts. Lost Threads is produced by two humans, Cameron Ezell and myself, Cory Munson. Thanks for listening.