Joy Flower

The opium poppy has been used by humans since the beginning of recorded history for both medicinal and recreational purposes. Wars have been fought and many lives lost over this flower. No matter how many times we try to change opium, history has a way of repeating itself.

The Shared History of Humans and Opium

Episode Transcript

Cameron: [00:00:00] Welcome back to another episode of Lost Threads. This is episode six. My name is Cameron Ezell.

Cory: And I'm Cory Munson.

Cameron: And today, Cory, what do we have to discuss?

Cory: My significant other was using this app called Seek, which basically just allows you to use your camera phone to identify any plant. And she was using on the different wildflowers that were starting to pop up, and she saw that one of them was a opium poppy, and I was really, really surprised that we had like a narcotic just kind of randomly growing in our yard.

Cameron: As far as I know, like in a lot of places, I think in Nevada it's fine. You couldn't grow a pot plant, but you can grow poppies without any problem. Right?

Cory: Yeah. I, I think it's, [00:01:00] it's weird. It's in this weird gray zone where it's tolerated. Even though it is illegal.

Cameron: And I think what's really interesting is when you look at that flower and look at, you know, the little white pill in Oxycontin that led to those Purdue Pharma trial settlements.

What happened throughout history, what led from us having that flower, to opium, to this pharmaceutical industry, uh, today, you know, it's a big journey.

Cory: Yeah. Because the first thing that needs to be established is every opiate comes from compounds that come from this specific flower. Opium isn't produced in any other flower or creature in the world.

It's only specifically this, this flower that was growing in my garden.

Cameron: And there's a lot more innovations in the medicine world involved around opiates than most would think.

Cory: The drug has been around since [00:02:00] before recorded history. I was curious where the poppy flower came from. Just like pigeons, it's from like the Mediterranean region, which also makes sense where its cultivation because that's where the first civilizations arose.

The first reference to opium comes from 6,500 years ago. It was on a Sumerian tablet, and the tablet refers to this drug, this plant, and they call it Hul Gil, which means plant of joy. On the tablet they just talk about how to harvest and prepare the flower for medical use. It, you know, if this tablet comes from over 6,000 years ago and it's describing cultivation like it's kind of common knowledge, we can only imagine how long before that people were actually using this flower.

Cameron: Yeah, I, I mean, I assume as long as humans and poppy flowers have been around, for the most part, there was probably usage of it as a painkiller.

Cory: It's [00:03:00] not terribly difficult to get like samples of it in nature. Like there's really not a lot of production involved. So like, basically all you need to do to get opium is you plant the seed.

Um, after 90 days, the seed will mature into this stem. It'll grow these petals. After a couple of days after it flowers, the petals will fall off and that will reveal this green fruit bulb. And inside of that bulb, that's where the, the opium is. There's like a latex in there that has a bunch of different alkaloids in it.

Opium, morphine, codeine. All you need to do to extract it is you just cut that bulb like a millimeter down and it'll start to ooze this latex out. Then you let that, um, air out overnight and then you can scrape it off. Basically at that point you have unrefined opium that you can eat or smoke.

Cameron: And I imagine because it is such a small, shallow cut, probably some ancient humans walking through a poppy field, some [00:04:00] bird or some insect had clipped a poppy bulb or something the day before.

They see this brown dried goop on this, uh, green pod and just licked it and maybe an hour later just started feeling amazing.

Cory: I just imagine that our, our ancestors basically ate or smoked every single thing that they saw in nature. Humans have been cultivating this stuff forever. The Greeks, the Egyptians, the Romans, they all used it.

It was just something that everybody knew about. It was there. It was used for medical purposes. I'm sure it was used for recreational purposes as well. Uh, there are quite a few references to the opium poppy throughout the Roman Empire. They widely cultivated it. They widely produced and cultivated it.

Cameron: They actually made little poppy cakes with like honey and opium and would sell those on the street to people as a way to just kind of [00:05:00] ease some aches and pains and help people sleep.

Cory: They used it for like diarrhea. They used it for coughs, indigestion, insomnia. It was used for a bunch of different medical ailments.

They do write in, uh, in some of their medical codexes that it can be abused and if you drink too much or have too much of it, it can plunge you into lethargy or death, they write. So they, they knew at the time that it was something that you had to be pretty careful with.

Cameron: Yeah. At at least they didn't have fentanyl.

Cory: Yes, they did not have fentanyl, but I was reading about a medicine that existed before the Romans, hundreds of years before the Romans. And, um, it, it was called a theriac. T-H-E-R-I-A-C. What this substance was is it was a, a conglomeration of dozens and dozens of ingredients. So they were bark, venom, opium, lavender, mint, honey, wine.[00:06:00]

It'd be, it'd be all of these different ingredients, and they were combined together to make this elixir. It was purported that it could basically cure everything from snake bites to depression, to colds and coughs, flu, like the perfect drug.

Cameron: Do you think that they could have really thrown anything in there and then just opium and then they would've seen it as a good drug?

Cory: But you have to remember too, that like these people were no dummies and they knew that a lot of different plants had different healing properties to them like echinacea.

Cameron: It would be like if, if honey is good on wounds and opium helps with pain and like you take all these different things and mix 'em together, how could it be worse?

Cory: Yeah, exactly. Like there's no downside to just packing everything that is beneficial to a sick person into, into one very powerful drug. Which, which is kind of funny too, because opium was tagging along [00:07:00] inside of these theriacs. But it would continue to have this narrative throughout history of like, what's the best way to refine this thing and to make it like the perfect drug that's not addictive and that makes people not feel pain.

Cameron: Spoiler alert. It's always addictive no matter what.

Cory: So opium was used forever throughout the middle Ages into modern day. But, but like, it, it, it basically, the process that I described earlier about how to harvest it and get at it like that didn't really change for thousands and thousands of years.

And it actually wasn't until laudanum was developed in the 17th century.

Cameron: And laudanum, right, is just basically opium plus alcohol.

Cory: Yeah. It's a, it's a solution of opium and alcohol, and it's a very simple way to ingest it and to, and to ship it. When it was first developed, it was developed by a Swiss physician named Paracelsus.

Paracelsus developed this tincture, and of course, since it's the Middle Ages, he's going to still add things that are unnecessary in there, like [00:08:00] pearls and gold dust. And then he aged the, the laudanum in dung. But by the 1700s it was simple. It was you, you put opium and suspend it in alcohol and you're ready to go.

It's much easier to just disperse this 'cause you don't just have to like smoke it or eat it anymore. You can literally just take a small little tincture. So by the 17, 1800s, opium is absolutely everywhere.

Cameron: And it, I mean, the British Empire at this point, they own poppy fields, mostly in India, right.

Cory: By this time that we're about to get into, they had subjugated the entire subcontinent and had access to these vast poppy fields in North India. Um, not only were the British in India, of course, they had the empire that the sun never sets on. They were all over the world, and their primary interest was [00:09:00] to open up as many markets as possible to sell goods that they were producing in their colonies for things that they couldn't otherwise get.

Now, the British were extremely successful at this, but there was one specific country, one specific target that had a ton of products that not only the British, but all European and North America and that, that they all wanted, but they couldn't get access to them. And that country is China.

Cameron: Okay, so Britain wants what China has, what does China have that Britain wants?

Cory: China produces porcelain. People in North America and Europe really, really like porcelain. China also has silk. Which was produced in other places, but not at the scale that, that China had. Basically, if you wanted fine silk and a lot of it, you had to trade with China.

Now, China [00:10:00] also had tea. Now everybody has tea in their kitchen, so it's, it's weird to think of this, this thing is something that was difficult to get a hold of. Tea originated in China. At this time when the British are starting to build their empire, tea was not accessible to them. There are a couple places in Southeast Asia and where you could get access to it, but again, just like silk on the scale where you are trying to provide tea for an entire empire that is becoming addicted to this new drink.

At first it was extremely expensive. Like only the rich people drank tea. They just couldn't get access to it. It was, it was so rare. Britain started to grow and develop and it started to have a larger middle class. And even the, the lower classes started drinking it. Like there was such a demand that they could not keep up and the only place that they could get their tea was from China.

But China was absolutely not interested in trading with Europe or the world outside of their little sphere of influence.

Cameron: Yeah, they didn't really need to, right? [00:11:00] Basically had everything they needed in their own country.

Cory: For us, it's like, why wouldn't you trade with them? Because you can get like cool things like guns and clocks and whatever the heck you want.

They really want your tea and porcelain and silk. Just, just, why wouldn't you give it to them? But it, it's, it's just such a different culture at this time. Them trading with these outsiders who won't recognize the emperor as being supreme to them and basically give patronage to the emperor and say, oh great China, um, can we trade with you?

Like the Europeans weren't going to do that. So for China, they were like, well, we have everything that we want. We have most of the world's population here. We don't want to trade with you. We have no interest in doing that. And also they saw a lot of the European products, for the most part as curiosities.

They weren't interested in the machines and, and whatnot. They, they had their own machines. So why, why would you trade for clocks the things that China did want? Like, there were, there were things absolutely like, [00:12:00] uh, sandalwood and fur from North America. There was a market for that.

Cameron: Another good from North America that China really wanted was tobacco.

And so that was something that China loved a lot and that's basically the only place you could get it was North America.

Cory: And, you know, it's interesting to compare Japan to China because we talked about Japan already. By this time they saw the writing on the wall and they, they knew they had to either innovate or become a, a colony of one of these European powers.

So right across the sea, Japan was adopting a lot of Western principles and they were opening up for trade and, and doing basically everything that the other great powers were doing. But China was not going to do this at all. It's not entirely their fault. Japan's a lot smaller than China. It was much easier for them to reform their society.

It was, it was a lot harder for them to adopt new ideas at the speed that the Europeans were expecting. But you know, we didn't mention the big thing that [00:13:00] China did want, something that they had a lack of, and, and that was silver. China used silver for its currency. Europe was flush in silver, and this was because of the Spanish.

The Spanish were prolific in their ability to colonize North and South America, and they tapped the vast silver mines all over the Andes and in Mexico, and they were sending back tons of silver for hundreds of years. So there's plenty of silver available. And Great Britain had access to the silver, so they were able to trade silver for tea.

And this went on for a little while. But the problem was that they gave China so much silver that. China started to experience these huge issues with inflation and their economy just started to really slump, so they stopped taking silver. So now at this point, yeah, you can trade them things like tobacco and fur, but at the scale that Great Britain wanted tea, there needed to [00:14:00] be another product that they could get into China to get that tea outta there.

Cameron: And I'm guessing because of the topic of this episode, that product had to be opium.

Cory: And what results from this decision is what's known as the Opium Wars. Notice I say wars.

Cameron: How far would you go for tea, Cory?

Cory: You know, I don't really drink that much tea. Like if someone makes me a cup, I'll have it. I I, I read the- are you a tea drinker?

Cameron: Um, no, I'm more of a coffee drinker. I'll have tea from time to time, like if I've got a little bit of a sore throat or something like that. But yeah, I don't, it's crazy to me that like all of this, uh, conflict kind of started over this addiction for tea, which I cannot comprehend personally.

Cory: I know, and it, and it also parallels American history too, because there's a lot of the, the formation of our country was based around access to tea. So this, [00:15:00] this leaf that you put inside of your drink that makes you feel buzzed for a little bit. It's such a huge part of British history. 84% of Britons drink tea every day.

Cameron: That is crazy. That's a huge amount.

Cory: Yeah. Do you want to guess how many Americans drink tea every day?

Cameron: God, probably closer to 25%. Maybe less.

Cory: I read 50% of Americans drink tea, but I don't really believe-

Cameron: okay. That's still, that's way more than I would've guessed.

Cory: Apparently four in five millennials drink tea almost every day.

But from this random sampling of two millennials doing zero I, I'm like, you like I'll use it if I'm not feeling good. Like I almost use it as a medicine. I don't certainly use it when I'm feeling sluggish halfway through the day.

Cameron: No, it just does not hit the same way coffee does.

Cory: Okay. So Britain has this idea, they're going to basically trade one flower for another.

They're going to trade their opium for tea, and this went on for a little while [00:16:00] legally. Because opium was seen as a medicine, like there was opium in China that was produced and and given to people that weren't feeling good, but Britain was introducing so much opium into the country through the ports that the Chinese, looking at this fledgling addiction crisis, had to say whoa, hold on a second.

You can't send this stuff here anymore. And they, they cut off the trade, which just pissed off the British because they were saying like, this is a, this is a free market. If there's a demand for this, you can't stop us from giving a product that your people want. But the Chinese saw this as a national security threat.

There are millions of people now addicted to opium in their country.

Cameron: Yeah. Some of the numbers I saw for that, by the way, by the late 1830s, about 1% of the entire Chinese population, which is about 4 million people, were addicted. And [00:17:00] near some of those ports where all the opium was coming in, uh, the number could actually be as high as 90%.

Cory: So by 1813, China bans all production, all importation, and all consumption of opium. You can't have it anymore and you can't use it anymore in the country. The result of that, like with any kind of a drug prohibition, is that the market just went to the black market and it thrived just as much as it had before.

They just didn't go through ports anymore. So the Chinese government couldn't benefit from any taxes off of that trade.

Cameron: One company that was still involved with this while it was illegal was the East India company, which I kind of see as like the Sacklers of today. They were like Purdue Pharma pushing this drug despite knowing the dangers.

Cory: Yeah. When we're saying the British, I think it's better to say probably the East India company. But it's such a weird thing to describe what the East India company [00:18:00] was because it was, it was that it was a company, but it was a company with like a military and with towns set up all over. They, they were acting in the spirit of what their, their country wanted at that time.

But yeah, they were, they were quite rogue. So now that there's this black market thriving, the Chinese government has to find a different way to crack down on opium coming into the country. So they get even more stringent. They start forcing foreign merchants out. They impound tons and tons of opium and they destroy it, and they formally expel British merchants from doing any kind of trade in the country.

So at this point, Great Britain's like, okay, well you don't want us to do a black market. So the only other recourse we have is to go to war with you. In 1839, British gunboats sailed up the Yangtze River with the objective to force China to open up their ports for opium trade. [00:19:00]

Cameron: And this first Opium war, uh, the first two actually were pretty much just easily won by Britain, right?

Cory: Yeah. China was no match for Great Britain in this war, and the, the empire was already on the brink anyway. China has a long history of different dynasties coming into power, and after a time the dynasty starts to stagnate and another group will come in and take over China and start a new dynasty and bring in a new Golden Age. So this has been going on for thousands of years, and this time the dynasty that was in power in China, the Qing Dynasty, they were on the ropes already. They were having problems with revolts and famine and overpopulation and inflation from the silver trade.

Their military was very untrained and pretty unmotivated to do anything against this encroaching European threat. China also just really lagged behind in technology, like they had cannons and they had [00:20:00] forts with cannons. They had good forts with cannons that could repel British advances, but those forts just weren't fully staffed and there was no cohesive strategy to stopping this threat from these gunboats and these British soldiers. There were only about 20,000 soldiers that the British brought into this conflict. China had 200,000 troops available, but they were absolutely pummeled. For two years, the British captured cities, captured ports, um, won every single conflict.

Cameron: Regardless, though, I, and I respect this, the emperor of this dynasty, he, even though they kept losing to the British, he refused to legalize opium 'cause he saw it as an evil and he saw it as a poison. He saw it hurting his people and so he only allowed the importation 'cause he knew he couldn't stop it.

Cory: The, the, the [00:21:00] solution to this, these outsiders totally demolishing them was just to open up the opium trade again.

That's all that British wanted. They wanted access to tea, and they wanted to get this product into the country that they could get the tea for. But yeah, the, the, the Qing emperor just didn't do it. The war ended with terms that were entirely favorable for the British. Like you said, the importation of opium was a term in the treaty. The British got five trade ports in China, including Hong Kong. They would hold onto that city until the late nineties. So now that opium was again available in China, the problem not only persisted, it got way, way, way worse. You have such a large percentage of the Chinese that are now addicted to this drug. In 1841, which is around the time the first opium war ended, there were about 2000 metric tons of opium being imported into the country. [00:22:00] 40 years later, that number had tripled.

Cameron: It's just so evil how they strong armed China into all of this.

Cory: So the second opium war that the British open up also involves France, because now France has problems with China and they want to get more access to China.

So France and Great Britain invade China again, and they just totally smash the Chinese. When the war is resolved, the terms are that not only is the import of opium legal and needs to be protected and managed by the Chinese, the drug also needs to be fully legalized in China 'cause it's still a crime to, to use it.

Cameron: It's just never enough for the British Empire, is it?

Cory: There was so much opium in China that, because the economy was just destroyed at this time, opium was used as a currency because that was something that had value. This whole time period from the start of the first opium war, which is what China today [00:23:00] considers to be the beginning of their modern history, they date it to the first Opium war. This time, the 1840s, all the way to Mao Ze Dong and his communist revolution. This is known as the century of humiliation in China.

Cameron: So they had this huge problem with opium. How were they able to fix it? Because obviously it's not as big of a problem today.

Cory: It's because of Mao Ze Dong when he did his great leap forward. When the empire finally fell and the communists took over the country, Mao came into power and he had some very specific steps he wanted the country to take in order to reinvent itself. For the opium problem, Mao was like, okay, well if you sell it, we're going to execute you.

If you produce it, we are going to come in there and plant different things, and if you are addicted to it, there's a mandatory treatment program we [00:24:00] have for you where we're going to send you to a camp and you are probably going to do hard labor.

Cameron: So you're saying fascism works?

Cory: It's a really interesting question because in a, in a democracy, you can't really, you can't do that.

You, you can't just kill people or just mandatory like impound addicts. But you know, like how China recently said that if you're under 18, you can only play games for like three or four hours a day.

Cameron: Um, oh, it's even less than that. It's online games and it's one hour a night on the weekend.

Cory: Yeah. So they, they saw this, they see this problem in their society and they're like, okay, well the way we fix this is, bam, like a really, really powerful, um, response.

So I guess, yes, Cameron, fascism works.

Cameron: I thought about that during coronavirus too. Like, it, it worked well in those countries where they are able to have [00:25:00] more power over these people and force these lockdown. I'm not saying that that's the model you wanna look to, but when you've got a crisis, uh, it certainly works.

Cory: For short term solutions, turn to fascism.

Cameron: Absolutely. So while some of these wars were going on, there was a lot of uh, medical breakthroughs that were still happening with opium. There was a lot of research being done with it by scientists all over Europe and North America. And just some definitions: opiates are any drug derived directly from opium, so something naturally that came from opium.

Opioids is a much broader term, which still includes opiates, but it it also includes synthetic painkillers like Fentanyl.

Cory: But Cameron, what I want to know is why does opium feel so good?

Cameron: Well, Cory, it's because physiologically our brain has these receptors for [00:26:00] endorphins like this feel good chemical. So like when you get a, a runner's high, or when you have sex or you hear a really good joke, you get these endorphins, they make you feel good, and opiates somehow trigger those same receptors.

So those feel good chemicals, they just turn up in the brain. Inside opium are all of these alkaloids, some of these early researchers found 'cause they wanted to know what is it that's inside the opium? Can we synthesize and break down opium into its raw elements and just get the feel good part?

Maybe we can get rid of the addictive parts of the opium plant and just get the feel good part. And that's what they were trying for. And what they found are these alkaloids. So alkaloids were discovered in 1806 by Friedrich Sertürner in Germany. And they're just a chemical family. They've got a common molecular structure and they're all bitter to [00:27:00] taste.

They can be derived from other plants, not just opium. You can get cocaine, you can get nicotine, you can get caffeine. And from the opium plant, you can get several, but the most important one that researchers found early on was, by weight, 10 times more powerful than opium when isolated and was named morphium, which we now know as morphine. So, uh, Sertürner was young and pretty much unknown at the time when he discovered these alkaloids, when he discovered morphium. So this mostly went ignored at the time. Uh, when he was researching this, he actually almost killed himself and three of his friends by overdosing on morphium, and he was forced to induce vomiting in all of them to survive.

I mean, early on they were trying to, they saw morphine as the solution to opium addiction, believe it [00:28:00] or not.

Cory: When the farmers are extracting opium from the poppies, they have that latex. About 10% of that latex is morphine. They can like get to that even on the field. All that they have to do to convert that latex into a pure opium, into a pure morphine, is they need to add, they need to cook it, they add lime, they add ammonium chloride. The morphine precipitates out, and you're good to go. You can do that in a vat next to your field, so it is not hard to get at.

Cameron: The reason that finding morphine was so important was that at the time physicians had this opium at their disposal that they were giving to patients to help ease their pain and make them feel better. But there's all these different people extracting the opium from flowers with different production techniques. You have different strengths. It's hard to dose. And so [00:29:00] morphine was a way that they could get a very pure painkiller, it could give them accurate dosing, and so it was a big innovation at the time.

Cory: Right, because if you're just going to be smoking the the latex, you have no idea like what the proportions are in that. So now you can produce this reliable drug at an industrial scale.

Cameron: Yeah, we, I mean they've known this for thousands of years, but there's like this narrow window where like you can't have too much opium or it kills you, but you also can't have too little or you aren't going to feel anything.

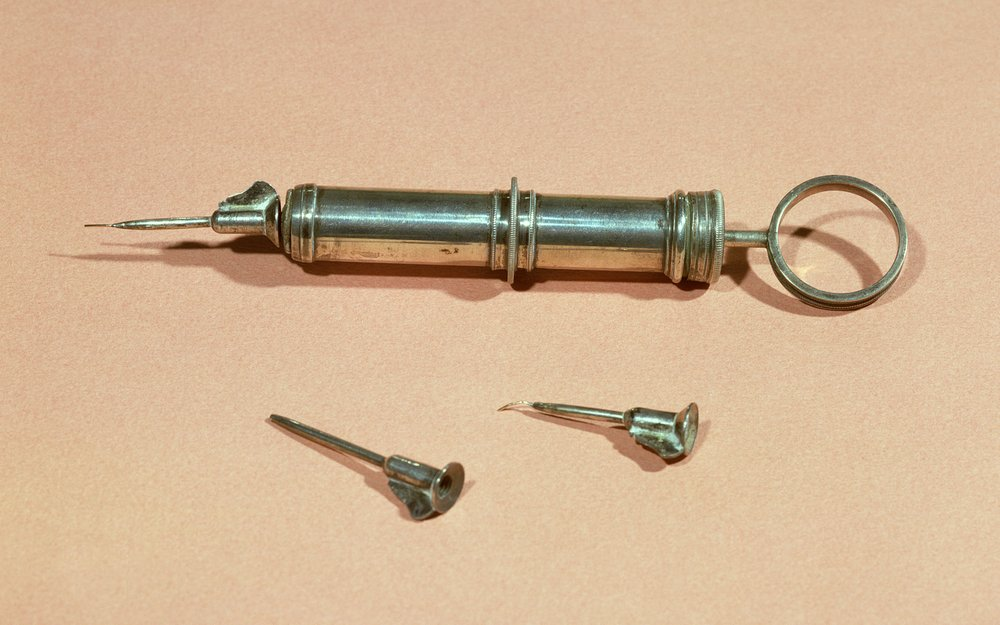

So it's a very difficult thing to dose out. And it also depends on your tolerance level, right? If you're an addict, you can handle a lot more than somebody who has never tried opium. With morphine came the problem of how to deliver it to patients. So now we can dose it out, but how do we give it? It used to be given by mouth or a suppository, but it [00:30:00] took a while for the effects to be felt this way.

So they tried powder to inhale it for patients, but it caused nausea. They tried smearing it on the skin, but this caused irritation and boils. They tried putting little balls of medicine in small incisions in their patients, but it was difficult to control the dose this way. So in 1841 along comes Charles Gabriel Pravaz who was a French surgeon, and he's working with this drug to slow blood clotting in patients, but the drug he's working with is destroyed in the stomach, so he needed a way to deliver the drug directly into the veins.

So he talked to a local metal worker, asked them to make a hollow needle out of platinum attached to a silver plunger, and so this would become the first syringe. But at the time, they were calling it the Pravaz after him, and this ended up becoming the perfect method for delivering morphine to patients.

[00:31:00] And like I mentioned, they, they thought that this would actually help opium addicts by weaning them off the drug with lower and lower doses. But why would that be? It's more powerful than opium and you get the, the rush of it immediately. So like, why would somebody just stop using opium or morphine?

They're just gonna switch to morphine.

Cory: I wonder why they didn't have people just smoke it. Can you smoke morphine?

Cameron: I don't know. I would guess that like inhaling the powder, it would cause nausea. Morphine became the drug of choice during the American Civil War, and I actually read that poppies were grown in home gardens across the US, both in the north and the south as a symbol of patriotism at the time for their troops.

Cory: It is a very pretty flower.

Cameron: It is. I, I like it a lot. So, uh, soldiers came in with a bullet wound, or they needed to have a limb cut off. The doctors were giving them morphine to ease their [00:32:00] pain, and at the same time, we're teaching them how to administer the drug themselves, because of course, during the 1860s, you don't need prescriptions for any of this.

You can just go to the store and buy morphine. So after the war, veterans just go out. They know how to give the themselves morphine. They just go buy it. And this created the first opiate crisis in America.

Cory: You don't need like a prescription for it.

Cameron: Not at that time, no.

Cory: Can you just go buy it from a a five and dime.

Cameron: You just go to a druggist. Aside from veterans, the typical morphine addict you would see in the 1870s was likely to be a woman. Because while men were enjoying tobacco and alcohol, it was kind of, uh, rude in society to, for women to be seen smoking and drinking. They could turn to morphine 'cause it was a very easy to hide habit.

In [00:33:00] 1874, a British researcher was experimenting and he attached a side chain of atoms known as an acetyl group to morphine. And when he tested the substance on some animals in his lab, he kind of came up empty handed. Like the animals just didn't do anything. It didn't really have any impact on them. But animals aren't humans.

Animals can't tell us how they're feeling. So it seemed like a dead end, but he wrote up a journal article anyway and just left it alone. We jump 20 years later. You may know a company called Bayer, right? They're known for their aspirin today, right?

Cory: Yeah. Dependable Old Bayer. I trust 'em.

Cameron: They're a German company and they were originally a dye making company.

In the 1890s, the dye making world was getting a little crowded and they weren't making as much money, so they decided to diversify. They thought, you know, we've got all these chemists, let's see what we can [00:34:00] do, uh, if we turn our attention to drugs. In 1897, one of Bayer's chemists was experimenting and just so happened to attach an acetyl group to morphine just like that researcher back in 1874. They didn't know about this research. So when this researcher attached this to a chemical isolated from Willow bark, he created a brand new drug that was good at reducing fevers and acting as a mild painkiller, and the company called it aspirin. So that's how Bayer aspirin came about.

And at the same time they developed aspirin, he had done that same technique of attaching an acetyl group to morphine. What he came up with was amazing when they tried it on humans. It was good at killing pain. It was good with coughs and sore throats. They thought this would be great for tuberculosis patients.

Bayer was [00:35:00] ready to sell this.

Cory: And also one thing that they were looking for was a version of morphine or opium that was not addictive. That was the perfect wonder drug.

Cameron: Yeah. I mean that was big part of research back then, just as it is today. I don't think we're ever gonna find that if it's gonna be an opiate.

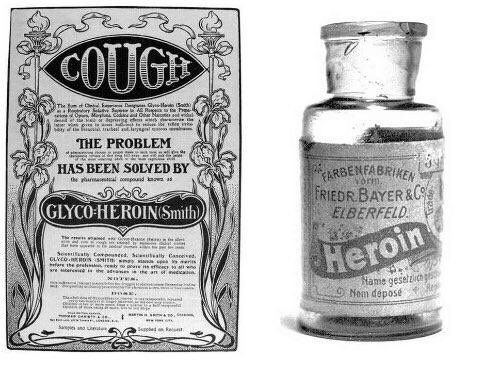

Cory: So by the way, what did Bayer call their new product?

Cameron: They gave it a name based off of the word for heroic in German: heroisch. So their new drug would be called Bayer Heroin. That is Heroin the brand name like a big H. And that's one thing that surprised me in this research. I didn't realize that heroin was a brand name.

Cory: It's like Coke or Kleenex, Heroin.

Cameron: You've got heroin, which is perfect for coughs and breathing disorders. It's a cure for morphine addiction. And uh, they started selling it. It was immensely popular. [00:36:00] Um, you could actually buy Heroin from the Sears-Roebuck catalog, for $1.50. And you would get two needles and two vials of Heroin.

The reason I brought up that story earlier of the researcher, you know, taking that acetylated morphine and just kind of disregarding it, um, that was a problem for Bayer. They discovered that there had been this research and all of a sudden there was no real patent protections on their heroin. So all of a sudden, all these other companies were able to start producing heroin.

Cory: Because Bayer couldn't keep it a secret because this research was just available for anyone to see.

Cameron: Exactly. So Heroin becomes heroin with a little H and that's when it stopped being a name brand. As kind of displayed by the fact that you can buy heroin from the Sears-Roebuck catalog, this was kind of the [00:37:00] wild West in terms of painkillers and any kind of drug back then.

Cory: And it's interesting 'cause in contrast to other things that people could take, like nicotine or alcohol, like this required lab work, like, it had to be produced in a laboratory. And the, just the fact that the people living at that time, politicians, could look around and see not only was like China addicted to opium, but like soldiers were addicted to morphine. Now this heroin was everywhere. Like it wouldn't be that hard to just say, okay, you need a prescription to have this.

Just don't sell it over the counter.

Cameron: It, it wasn't really until Teddy Roosevelt's administration where we first saw drug control laws in the US. The one that really started cracking down on narcotics in the US was the Harrison Act of 1914. What this did was [00:38:00] regulate and tax production, importation, and distribution of narcotics.

Narcotics, I should mention is like defined as anything that kind of makes you lethargic. And so the law actually had to call out cocaine by name because that doesn't fit the description of a narcotic. We generally call any kind of hard drug a narcotic these days.

Cory: It's interesting to me that we're only about a hundred years into figuring out in successful societies where drugs are easily accessible and easily produced, how do you limit your populace from partaking in them?

Cameron: And the Harrison Act was really effective at doing that too. So for the first time, it forced people to buy any kind of narcotic from doctors and pharmacists. It also forced doctors and pharmacists to register with the government, pay fees, and keep a log of every single [00:39:00] transaction involving opium, morphine, or cocaine.

And so this led to a lot less prescribing because all of a sudden you don't want the government looking at a log book and seeing, oh, I gave Bob here opium every single day last week, and when he overdosed.

Cory: Then, like now, I'm assuming it probably wasn't very difficult to get a prescription for painkillers from your doctor.

Cameron: Right. I, I cannot imagine that it was that difficult compared to today. Back in, you know, mid 2000s It was incredibly easy when our pharmaceutical industry was really pushing Oxycontin and things like that, so I can't imagine it was that difficult.

Cory: I think in 2017 there were more prescriptions for opiates than there were people in the United States, meaning those who had prescriptions, had multiple [00:40:00] prescriptions.

Cameron: Oh yeah. That does not surprise me at all. By the time World War I rolls around, there's still some innovations trying to take place in the medicine world in terms of opiates, and we get semisynthetics. So these are still derived from the opium plant, so we're still connected to that opium poppy from ancient Sumeria, but we're manipulating it in some way with a lab made chemical.

Codeine, which is an alkaloid that you can get from opium, you can manipulate that to become hydrocodone. If you manipulate morphine in the same way you get Dilaudid. If you, uh, mess with codeine, you get oxycodone. Which is the main ingredient in Percocet. So the, these drugs, hydrocodone, Dilaudid, Percocet, these start coming out around the World War I to [00:41:00] World War II.

Cory: And I'm assuming all these drugs, all these derivatives of opium, target different ailments, right?

Cameron: Yeah. I mean, it's all kind of seen as another method of killing pain. There's different uses. Obviously codeine is not so much a painkiller as it is for, uh, suppressing coughs. Those semi synthetics end up becoming fully synthetic opioids, which was a huge innovation because for a long time, scientists have been looking at the molecular structure of the chemicals in the opium poppy and trying to find some kind of substance that mimics what it does without being an opiate. And so some scientists in Germany in the 1930s, they were trying to develop a drug to ease muscle spasms.

They gave this to their mice, and the mice started getting an S shape in their tail. [00:42:00] One of the researchers had worked with lab mice and opiates and recognized this same thing. When you give an opiate to a mouse, it gets like this S curve in its, uh, tail. This was not an opiate. This was a fully synthetic substance that was created in their lab.

Cory: Meaning they are not using the flower in any way now.

Cameron: Correct. The molecular structure was unlike opium at all. If you looked at 'em under a microscope, they're nothing alike. The other interesting thing is that most opiates kind of make you sleepy and lethargic, and this made the mice very energetic.

They thought, this is interesting. What if we had have created a synthetic opiate that energizes you, and they called it pethidine. What this did is led to the discovery of methadone. Methadone was seen [00:43:00] as this huge innovation in helping addicts for the first time in a long time because methadone is something that isn't all that pleasant to take.

It gives you a little bit of nausea. You don't really get high at all, but it soothes the symptoms of withdrawals.

Cory: It's kind of like the nicotine gum of the opioid world. It's not exactly what you want, but it takes the craving away.

Cameron: Yeah, no smoker wants to like finish a big meal and sit back in their chair and put in a stick of nicotine gum. That's what this is. Essentially, methadone is nicorette. The problem they had, you know, the researchers wanted to get these patients completely off of their opium addiction, but they're never able to fully wean themselves off of it. They just hit this wall. So they can just keep giving them less and less methadone, but it reaches a critical point. [00:44:00] And so the idea became just to keep people on methadone for the rest of their lives. And we still have methadone clinics today. I still think that, you know, they're helping people, but it really isn't the panacea that people thought it would be.

Cory: Maybe it should be like fluoride where we just put it in the water supply.

Cameron: Just make everybody miserable and addicted to water. This brings me to this researcher named Paul Jansen, who was studying the molecular structure of natural opiates like morphine with synthetic opioids like pethidine, and found that they shared a structure in there called piperidine, and he believed that this is what gave opium its " spirit".

His lab began creating new drugs, and in 1960 they created a new drug that was more than a hundred times stronger than morphine, and they named it Fentanyl. As we know, fentanyl is incredibly [00:45:00] addictive and very deadly. Very potent, right?

Cory: Like just a couple grains of it can kill somebody.

Cameron: Yeah, you do not need much fentanyl, uh, to ease your pain.

But it's just, I wanted to look back at this history we've brought all the way up to fentanyl. So, you know, we've got the opium plants and inside opium you've got an alkaloid called codeine. And if you manipulate codeine, you get Percocet. And if you create this time released formulation of Percocet, you get Oxycontin.

That is what Purdue Pharma just settled. You know, we're still, we've talked about the opiate crisis that happened during the American Civil War. We're still dealing with an opiate crisis here in America. You know, we keep seeing these quote unquote innovations take place that are supposed to create this non-addictive, [00:46:00] beneficial version of an opiate that never will happen.

We're always gonna have problems with opium.

Cory: It brings me back to the theriac we were talking about, which is supposed to be a philosopher stone drug that you take it and it cures every ailment that you might have. And we are still looking at this flower to provide that for us. But it seems like every time we innovate it, it just digs us deeper in that hole.

Cameron: And when we say "we", it's more to do with the US. The United States has 5% of the world's population, but consumes about 80% of the world's prescribed opioids. I would like to mention, you know, a lot of my sources came from the book 10 Drugs: How Plants, Powders, and Pills Have Shaped The History of Medicine by Thomas Hager.

Uh, we'll have links to some of our [00:47:00] sources. We'll have some pictures on our website lostthreads.org. Uh, is there anything else, Cory?

Cory: No, thanks a lot, Cameron. You answered my question about why there was an opium poppy growing in my garden. Don't do drugs, folks.

Cameron: Don't do drugs. Stay safe. Catch you next time.

Sources:

“Ten Drugs: How Plants, Powders, and Pills Have Shaped the History of Medicine” by Thomas Hager