Plight of the Pigeon

While today they're often seen as a nuisance within cities, pigeons were once one of man's best friends. In today's episode, we discuss the role that domesticated pigeons have played in the lives of humans over millennia.

The Shared History of Humans & Pigeons

Episode Transcript

Cameron: [00:00:00] Welcome back to Lost Threads here for episode four. My name is Cameron Ezell.

Cory: And I'm Cory Munson. Cameron?

Cameron: Mm-hmm. What's up?

Cory: I have a little word association game for you.

Cameron: Okay.

Cory: What comes to your mind when I say the word dove?

Cameron: Uh, Home Alone to Christmas, religion, angelic, that kind of thing.

Cory: Now, what comes to your mind when I say the word pigeon?

Cameron: Rat with wings. Filthy. Cigarette-eating. New York. I don't know. They're disgusting.

Cory: Oh, Cameron, so easy to fool. Those are the same exact animal, the dove in the pigeon.

Cameron: Okay, but doves are way prettier than pigeons.

Cory: Well, it's kind of like saying a Chihuahua's way [00:01:00] prettier than a Great Dane, which isn't true.

Cameron: Well, it is true. Maybe you can try to convince me that they're not trash birds.

Cory: Well, Cameron, challenge accepted because today we are going to be talking about the sordid history of probably the most maligned bird, the pigeon.

Cameron: Except for maybe seagulls.

Cory: What does it mean if I say that an animal is wild?

Cameron: It has lived and all of its ancestors have lived in the wild that isn't really domesticated. I guess we'll get into that term.

Cory: Exactly. They do fine on their own. They can live their entire life without ever seeing a human or being exposed to human society. Let's talk about tame. If I say that an animal is tame. What do I mean by that?

Cameron: Um, I assume it's still a wild animal, but it's not going to lash out and hurt me.

Cory: They tolerate humans being around like park animals, probably rats and mice that live in cities too. Not intention-

Cameron: Make them famous like pizza [00:02:00] rat.

Cory: I don't know who that is.

Cameron: It was like an internet video meme from like seven years ago of just a rat carrying a big slice of pizza up the stairs from a New York subway.

Cory: Oh. So while we're talking about rats, like, you know how all dogs come from the same species of wolf.

Cameron: Kind of.

Cory: So, so all dogs come from the gray wolf, like there are a bunch of different types of wolves out in the wild, but every dog that you've ever seen is descended from one specific type of wolf that got really, really close with humans 10,000 years ago.

And everything from a chihuahua to a Great Dane. Wow. Those are the only two dogs that I can list today. But all dogs descend from one single ancestor, so, if you have any domesticated rats, it's the same thing. It's not like you can just grab any random rat and then breed it long enough and it'll be okay with humans.

It, it's a very specific type of rat. It's a Norwegian [00:03:00] wood rat. Um, and so if anybody has any domesticated rats today, it's because it's, it's specifically from that animal. Let's move to the next category, which is feral. What does it mean if an animal is feral?

Cameron: It's an animal that can be domesticated, but is just out living in the wild. Kind of like you find feral cats in an alleyway.

Cory: Yeah, like its ancestors were domesticated or even maybe its parents were domesticated or maybe it grew up in a house and it became a stray and it no longer lives under the rules of a human household, but it does have all of the, the DNA of A species that was once domesticated.

Like when I found you in the woods 15 years ago and I raised you and you know, I taught you the arts and I taught you language.

Cameron: Suckled me back to health.

Cory: I'm very proud of you. And then the last category is [00:04:00] domesticated. So that's one that we're gonna be talking about today. But let's just simply say that domesticated means that the animal, whatever species it is, and humans have a very close relationship. That the offspring are selectively bred, like you know how people will have pure bred dogs and they will breed those dogs to get a desired trait. And that humans have been doing this over millennia. So the reason that I want to talk about pigeons today is because I can't think of a topic that deserves the title "Lost Thread" more than the pigeon.

Every single pigeon that you've ever seen in a city is a feral pigeon, meaning that they are all descended from a very specific species of pigeon that was once domesticated. Domesticated in the same way that dogs and cats and pigs and cows are domesticated. The pigeons that you see in cities are not wild pigeons.

They are feral [00:05:00] pigeons. Now domestication has happened to a lot of things during humans life after the Ice Age. Humans have domesticated plants. They've domesticated animals, insects. Animal domestication, meaning humans adopting animals into their own society and slowly starting to change what those animals were like in order to get a desirable product or trait out of that animal that served humans, that started about 10,000 years ago and the very, very first animal that humans domesticated were dogs.

Cameron: And I'm glad humans did domesticate them because, uh, now I have three dogs myself here at the house.

Cory: Would you say you love all of your dogs equally?

Cameron: Of course. Yeah. We've got Daisy, we've got Waffles, and Maeby.

Cory: Humans domesticated dogs, not really for their meat or, because no one drinks dog milk, as far as I know.

Cameron: Ugh.

Cory: Dogs were mostly brought about because [00:06:00] of their ability to assist in hunting and like their security. If you've ever gone on a walk in an urban area before, you can definitely attest that dogs don't enjoy having anybody come near their territory, and they will let you know that they're not happy about it.

So, dogs barking to alert people that someone was coming near, like that was a really useful thing for early man to have. A little bit later on about 9,000 BCE, uh, sheeps and goats came about. Humans really liked having sheeps and goats around because they provided everything that our early ancestors needed, like wool and milk and meat.

They were like walking textile and meat factories that could be shuffled around wherever. 7,000 BCE cattle and pigs came about. They have a ton of meat on them, so you know, put them in a pasture, they ate as much as they wanted, and then you could slaughter them and eat throughout the winter.

Cameron: It is kind of crazy to think that before we domesticated cattle and pigs, that our ancestors would [00:07:00] have to go on these grueling hunting trips in order to get their meat, which could take, you know, a day or two just to bring home a carcass.

Cory: So by about 3000 BCE, cats, horses, donkeys, and camels start to become domesticated. And cats are kind of interesting because there's not a lot of, there's not a lot of domesticated animals that are carnivores because it has to eat other animals in order to get big and strong. And if- so, you have to farm those other animals for your carnivore to eat.

Um, and it's just really, really inefficient because those animals have to find pasture to eat. So why, why don't you just work with the animals that eat stuff that comes right out of the earth instead of having the secondary tier? Humans never had cats around for any other reason than to hunt mice and rats that were, you know, in their houses and in their towns.

But other than that, they really didn't serve any purpose like the other domesticated animals.

Cameron: Now, can you speak to the theory that all [00:08:00] dogs are boys and all cats are girls?

Cory: Oh, excellent question, Cameron. That came up in my research quite a bit, and I can definitively say that it does seem that if I'm reading it right, both species do have both genders in them.

But it's confusing because feline does sound like female and it is really easy to see a dog's penis.

Cameron: Yeah, easy for you.

Cory: So, so that's a basic timeline of humankind's domestication of animals. But, you know, we're talking about pigeons today, and the question is, where, where do pigeons fit into this timeline?

How long have pigeons been domesticated? Well, it, it's kind of hard to establish that with birds. Bird bones disintegrate and they don't hold up well in archeological records. So, I mean, that's a rough estimate based on writings or, or paintings or whatever. Um, there's research that says that pigeons have been domesticated anywhere from 3000 BCE [00:09:00] to 7,000 BCE, you know, which is right up around the time that cattle and pigs were domesticated. So the point is, pigeons have been with humans for a, a very, very, very long time, and they were intimately linked to many early civilizations.

Cameron: So you mentioned before that all dogs are descended from specifically the gray wolf, right?

I'm just wondering how that even begins.

Cory: That's a great question. My answer to that comes out of the work of Jared Diamond, um, who wrote "Guns, Germs, and Steel". And in in that book he does talk about why certain animals can be domesticated and why some animals can't be domesticated. Really, it turns out that the list of animals that humans can actually domesticate is pretty darn small. So you know, there's thousands of species of birds and, and animals and insects, but most are not able to be domesticated. And it's like, [00:10:00] it's not like for lack of trying. Humans have tried to domesticate basically everything out there from cheetahs to bears to zebras.

If an animal is still wild, like a zebra, there's a good reason for that. So there's like a lot of traits that the animals need to have, and they need to have all of them. You can't have four of the traits and then not have the fifth. You have to have all of them. And, and so that doesn't really apply to most animals.

Um, I'm not gonna go over every single one, but the first one is that they can't be very picky eaters. Like koalas need to have one type of food all the time.

Cameron: Right. They only eat eucalyptus, right?

Cory: Yeah. And you know, if, if an animal only likes to eat one certain kind of meat or one certain kind of plant, that makes it really, really hard to have that animal kind of grow in large populations.

Cameron: Joe Exotic, the Tiger King, domesticated his tigers and they just ate Walmart hot dogs.

Cory: Joe the Tiger King tamed his tigers. There is no [00:11:00] domesticating a tiger. Well, so that, that kind of brings me to the next one, which is they need to be comfortable breeding around humans. And the example that Jared Diamond uses for this one is cheetahs. So humans forever have been trying to domesticate cheetahs, because how cool would that be to just have this pen of gigantic house cats that can go 60 miles an hour and join you in battle? But cheetahs are really, really weird about their sex life. They don't wanna mate in an enclosure.

Their mating ritual consists of them like sprinting across the plains at high speeds for long distances, um, in order to do their courtship. So with, with a mating process that complicated, it's really hard to accommodate that, and it's very, very hard to breed cheetahs in captivity. Another thing that animals have to have in order to be domesticated is they need to have some sort of a pack or a herd mentality that, that they would be able to imprint upon [00:12:00] humans the, the role of a leader or the, the head of the pack.

The only exception again, is cats. They're generally solitary hunters. It's really weird that cats decided that they wanted to be domesticated. I don't completely understand it.

Cameron: Yeah, that doesn't make much sense. Maybe they just, maybe they're just brilliant and they just found a really good deal.

Cory: Well, I mean, yeah, right.

Like they're like, I'll hang out with humans and I'll get all the rodents that I want, and then they will try and curry favor, but I might give it or I might not. The last one is that they have to like being around humans and they can't be too aggressive or too panicky. So like with the example with the gray wolf, it could just be that out of all the other breeds of, of Canids and out of all the different types of wolves, those ones had a predisposition to not being as afraid of humans and was willing to approach, you know, early stone age [00:13:00] man.

And, um, over time they were, they got more and more comfortable. It was just some quirk in them that led them to do that because obviously none of the other breeds of wolves decided to go down that path. But like you can't domesticate a bear or a lion 'cause they are just way too aggressive. You can't domesticate a zebra or a deer because although they follow a lot of the other qualities that we've talked about, zebras, it turns out, are just nasty.

I mean, you know, zebras look like horses. They're basically the cousin of the horse, but you can't domesticate them because they will just try and bite you. They do not like to be handled at all.

Cameron: I still remember going to the San Diego Zoo as a kid and being terrified of going near the zebras because one of the zookeepers told us that if they bite your finger, they won't let go until they've got your finger off of your hand.

Cory: Oh my God. So let's get back to pigeons. They tick all of these boxes. They [00:14:00] enjoy eating, whatever, and they'll gladly eat whatever humans throw out. They don't mind making-

Cameron: Like cigarette butts and band-aids and used needles.

Cory: Well, you know what? Is that the pigeon's fault or is that the human's fault for deciding that that belongs in the street?

Cameron: You're right. We're the virus.

Cory: Like they don't mind mating in public and they don't mind mating around humans. They actually don't mind being around humans at all. Like if you, uh, you know, we're talking about feral pigeons in cities, which are, which were once domesticated, so they're even more chill. But like you can sit on a park bench and a pigeon's just gonna walk around your feet and not even notice that you're there.

They are really social animals. They love being around other pigeons and they love being in groups and you know, they will follow a leader. So they were absolutely ripe to be domesticated. So we talked about like why the humans might like to have a dog around or a cow around, or a pig around or [00:15:00] whatever.

But humans love to have pigeons around for three reasons. The first reason is that they're nice pets and if you, you know, they can be selectively bred just like a dog can, and you can try and get certain traits out of the offspring. You can make really, really attractive and good looking pigeons. We're not talking about the the ash gray pigeons that you'll find in a city.

Cameron: Yeah. You sent me a link to a bunch of different pigeon breeds that were really cool and crazy looking.

Cory: Yes, we will post that on the site. It's, um, from the American Pigeon Museum, which is in Oklahoma City, but they have a whole gallery of domesticated pigeons, which are just, I mean, they run the gambit.

There are some beautiful, beautiful ones in there with like purple metallic sheens on their necks, or kind of big, uh, bell bottom pants that are just, you know, feathers. There's some really neat looking ones. So the second reason [00:16:00] that humans wanted to domesticate pigeons is that pigeons can provide a pretty reliable, uh, source of meat.

This was probably the biggest reason why humans originally liked having pigeons around, is you can, you can eat them.

Cameron: I still can't wrap my mind around the idea of eating like a city pigeon.

Cory: No.

Cameron: I know that's not what you eat, but it's just I can't get that image out of my head.

Cory: The third reason that humans liked having pigeons around is also the coolest.

Pigeons have a very, very unique and almost mysterious ability. They are able to return to their home nest, even if they are hundreds of miles away in unfamiliar territory.

Cameron: It's almost like a superpower.

Cory: It, it is like a superpower. Let's talk a little bit about what we mean when we say pigeon. So there are actually hundreds of species of birds that classify as pigeons or doves.[00:17:00]

In fact, there's a whole bird family dedicated to pigeons. It's Columbidae. So like you've got tropical fruit pigeons, you've got crested pigeons found only in Australia. The Dodo is actually a member of the pigeon family.

Cameron: Poor dodos.

Cory: So like, although there are hundreds of different types of doves and pigeons, only one species would end up being domesticated by humans.

And that species is called the rock dove. So most species of pigeon are wild. You've probably maybe seen one, um, at some point, especially if you were out far away from a city, but I will guarantee almost every single pigeon that you see in the city and the pigeon that pops into your mind when I say the word pigeon is a feral rock dove pigeon.

Cameron: So which, which part of the world specifically did rock doves come from? Where are they native to?

Cory: They're actually from North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean, which makes sense because that's where the early human civilizations [00:18:00] were that first domesticated them. There's still plenty of wild rock doves around today, and as their name implies, they like to hang out and nest in rocks.

Um, specifically like vertical cliff faces, they like to live in little alcoves. So like at some point 5 to 9,000 years ago, rock doves started to notice human civilizations popping up in Egypt and in and in Mesopotamia, which is where modern day Iraq is. And just like the gray wolves, they were very social and friendly and they weren't very bothered by humans.

They liked all these big buildings that humans were making, you know, city walls and large edifices and they decided, "Hey, this is kind of like our own natural territory", and they started to put up residence in early human societies. Over time, the humans and the rock doves started to co-mingle and they created a little bit of a symbiotic relationship.

And so over time a new species of pigeon was created that descended from these rock doves, which is [00:19:00] Columba livia domestica, or the domestic pigeon. The difference between a dove that you use at a wedding and a city pigeon is the same difference as a golden retriever and a Labrador. They're the same exact species.

They just have, uh, a different cosmetic look to them.

Cameron: The dove that likes to hang out in our backyard is maybe the biggest pigeon I've ever seen. It looks like it could weigh like 40 pounds. I know it doesn't, but it's huge.

Cory: Well, that's interesting that it's kind of nested up with you.

Cameron: Well, we'll see how long since we're selling this house.

Cory: Maybe it'll follow you. No, it won't follow you, but if you drove it down to Las Vegas and then released it, it would probably go right back to your house.

Cameron: That is really crazy to think about.

Cory: Most rock doves were just raised for food or sport. Um, like even from the ancient era, pigeons were used in races and they were used as decoys for hunting birds of prey.

But, but let's, let's talk about food for a second. It's really strange to, as you like, as you said earlier, it's really strange [00:20:00] to look at feral pigeons today in the city and think like, I want to eat those. But they were a huge food source for a lot of early civilizations. Um, even up to the medieval ages, like you hear like a pigeon pie.

Um, if you get a chance, look up something called a columbarium and I just sent you a picture of one Cameron, so you can see what I'm talking about here.

Cameron: Yeah, super cool looking.

Cory: Yeah, so it's basically like a- most of these were underground, but you could make these out of like a mud or stone tower, but it's an underground cave that is just pocked with hundreds, thousands of these little alcoves, and it kind of simulates what a rock dove would have in the wild.

Where they like to just hang out inside of a cliff wall. But these are like pigeon farms and there's just enough space in these alcoves for, um, a mama pigeon to lay its two eggs and two 'cause they always lay two eggs and to raise those two pigeons. And yeah, I mean, when these were in their prime, the, the ones [00:21:00] that we're going to show were just ancient excavations from, um, specifically ancient Israel, because Israel had a bit of a covenant with the pigeons because there, there weren't a lot of animals that they could actually sacrifice, but pigeons were definitely one of them. Um, but also they were, like we said, a, just a fantastic food source. So you'll just see these gigantic columbariums filled with thousands of these holes.

Um, and I just imagine that in its day it was a, it was kind of a sight to behold. It.

Cameron: I mean, it doesn't attract pigeons today?

Cory: They might, I mean, a lot of these are kind of crumbling and they're just tourist attractions. Now, the other cool thing about these columbariums is that people were able to harvest, you know, pigeon droppings.

And today we see those as an anathema, but they were, I mean, it's free fertilizer, right? Pigeons go out, they eat whatever they want, they produce droppings, and then you just put that on your crops and bam, you're good to go. You got your phosphorus. Now pigeons have been eaten for thousands of years, but some listeners might be surprised to hear that [00:22:00] they are still eaten today.

It's a little bit of a taboo just based on the conversation that we are having kind of squeamish about even the thought of eating those things.

Cameron: I, I remember going out to Chinese restaurants when I lived in Boston and Squab was always on the menu there. Which-

Cory: what is it? Just, what's it called?

Cameron: Squab. S-Q-U-A-B. Squab. And it's just another name for pigeons that you eat.

Cory: Have you ever had it before?

Cameron: I haven't, because I just can't get that mental block out of my mind about just eating what is essentially, you know, the rat with wings that I mentioned earlier.

Cory: I hear it's really, really good.

Cameron: Yeah, I, I've heard it's good.

It's, you know, kind of gamey, don't prepare it like chicken. And there's very specific things you have to do to raise squab. If a pigeon can fly, which it can after about maybe like four weeks, um, it's too old to eat. It just tastes disgusting apparently.

Cory: Wait, so squab is [00:23:00] like veal?

Cameron: Kind of, yeah, just really young pigeon.

So they're small and they're typically cooked to medium rare, which, you know, kind of sounds gross when you're talking about eating chicken or something like that. But you're not going to get sick from eating medium rare pigeon. If you cook it beyond that, apparently it has, uh, tastes more like liver.

Cory: Okay, so let's get into the real squab of this episode and talk about the thing that makes domesticated rock doves so freaking cool.

I talked about it earlier, it's, it's their homing ability. There are, like I mentioned, there are hundreds of other species of dove and pigeon and some of them can home, but definitely not all of them. And of the ones that can home, rock doves are, from what I gather, are just the kings of it and they, they might even be the kings of doing it in the animal world. In all the research that I did, I couldn't find anything that even compared to what rock doves can do. [00:24:00] Like a lot of animals, even besides birds, have some sort of a homing ability in them. Like birds are known for migrating from one place to another. Turtles and salmon are famous for being able to return to the same place to do their spawning. And I even feel, I don't know if you feel this too, but like when you are in a parking lot, you might not know where your car is, but you have like a general sense. But like what those animals do like does not compare at all to what the rock dove does. You can take a trained homing pigeon, and just to clear this up, a homing pigeon is just a domesticated version of a rock dove. You can blindfold it, drive it out 200 miles from where you started, let it go, and it will easily be able to return to its nest. Given the right conditions, they can probably do a much larger distance than 200 miles.

Oh, have you ever heard of pigeon racing before?

Cameron: No. That's, that's interesting.

Cory: It is really cool. Let me explain kind of [00:25:00] how it works. So it's, it's a pretty popular sport and the way it works is competitors gather in one location with all of their well-trained homing pigeons, and then they release the pigeons all at the same time.

The pigeons homing sense kicks in and they all race back to their home base. During these competitions, racing pigeons can find their home over 3, 4, 500 miles. In the United States, it seems like the largest tracks are 600 miles. Um, but there's some all over the world. There are some in like Europe and Asia, which can go up to a thousand miles.

And basically if your pigeon gets there first, then you win the prize money. And there can often be a lot of, a lot of money at stake, uh, during these competitions. I read that the most difficult track in the world is, uh, it's a 350 mile race on the, it's between the Leyte Islands in the Pacific to Manila in the Philippines.

I don't know how true this is, but I read [00:26:00] that only about 10% of the pigeons actually make it to the destination due to unpredictable winds and like the risk of getting killed by predators. Seems like a little bit of a blood sport.

Cameron: Yeah. Considering how expensive these pigeons can be. It's like if the Kentucky Derby race was like the last horse surviving and it's just these million dollar horses just dying.

Cory: I know. It's kind of sad, right? Because pigeons are really smart and they have just as much a right, you know, to live and to to survive as any other animal. But I guess because they're small and they breed pretty fast, you're not too, I mean, I'm sure the owners don't want their pigeons to die, but I guess why would you send your beloved trained homing pigeon on a, on a track like that?

Cameron: Do they know why it is that? Pigeons are able to do this or know how it's done.

Cory: No, that's the cool part. People aren't actually sure how pigeons are able to home like this. There's a couple of theories of course, but there's nothing really [00:27:00] definitive. It seems like pigeons are able to put together a lot of different pieces of information in order to home so accurately. Like the first one is that pigeons are able to track the position of the sun and just use that as a reference point. However, pigeons are also able to travel at night, so there's other things going on besides the sun. There's quite a bit of research that pigeons are able to detect the earth's magnetic field.

And another cool part of that, uh, well maybe not cool for the pigeons, but back in the 1930s, people in the military were discovering that pigeons were often pretty confused when they were confronted with radio waves or radio towers. They kind of lost their orientation, but not all pigeons did. So again, you can't definitively say that they use magnetic fields.

There's another theory, which I think is really cool, and it says that pigeons are able to create an olfactory map. So basically like while they're flying, they pass a farm, they know its smell and they build a little bit of a smell map. They pass a factory, they know its smell. Over time, [00:28:00] they're able to know exactly where they are just based on the smells that they're picking up in the atmosphere.

The final one is that pigeons are really good at recognizing landmarks and, and I just wanna establish this. If you take a pigeon that just learned how to fly, you blindfolded it, drove it 200 miles out, it would probably not be able to find its way home. Like you have to be able to train pigeons to do this.

They have to be allowed to fly around the area near their coop in order to get a sense of where it is exactly.

Cameron: But they taste horrible at that point too.

Cory: So it's, it's cool enough that you can race them, right, release them all at the same point, see which one gets home fastest, but early humans found that there was also a much more practical reason to use pigeons.

So let's say you're an ancient General. You can take a bunch of pigeons with you that have their home nest in your capital city, and if you ever want to send a message back home to your king or to the city, all you have to do is write a message on a small [00:29:00] scroll, tie it around the pigeon's leg, let it go.

And its innate sense is that it needs to fly back to its home. So it will, no matter where you are, be able to return back to where it came from.

Cameron: That's such a cool method of communication too.

Cory: I, I read that you can train it to go back home, but then teach it that it's food supply is with you.

So with the same pigeon, you can have it fly, deliver a message, get a message at that place, and then return back home to get its food.

Cameron: That's really cool.

Cory: So humans have been doing this for a really, really long time, and I would argue that before the internet or the aircraft very recent until very recently, pigeon mail was probably the fastest way that humans had to deliver a message.

So this is kind of silly, but I just wanted to highlight this story. Um, I wanna share a quote from an article from 2008. Um, there's a company in South Africa called Unlimited and it wanted to protest the slow [00:30:00] broadband connections in South Africa. It released a pigeon that traveled back to another one of their offices about 60 miles away, and they tied a USB stick to it, and they wanted to show that the pigeon was faster than broadband services in South Africa.

So this is from the article. Winston the pigeon took just one hour and eight minutes to fly the 60 miles between Unlimited offices and that time, just 4% of the data transferred via broadband. Even with an hour to upload the data from Winston's encrypted four gigabyte USB stick, it was quicker than the six hour transfer speed.

Cameron: Wow. I wouldn't want to play an online game that way though.

Cory: I don't know. I bet some old English gentlemen used their pigeons between castles to play a game of chess. You have returned, unfurled the scroll bishop to A3. Oh, you clever devil. So pigeons were used by kings and generals in ancient times.

The ancient Egyptians used pigeons [00:31:00] to declare like who the next Pharaoh was and send that information throughout the land. The Mongolians did it really well. At the height of their power, they had hundreds of pigeon posts throughout the empire that were just, they were able to quickly relay information and, and contact distant generals and and distant cities.

The ancient Greeks famously, after the Olympic games were concluded, they would release pigeons that would go back to their towns all over Greece, and they would announce the winners of the games. But some of the most famous stories about messenger pigeons, homing pigeons, come from modern war. Probably the most famous example of pigeons serving a critical role in a war was during the Franco German War of 1870.

It was a continental war against the two major land powers of the age, which were France and Prussia. Basically, Prussia got a huge confederacy of German principalities, they invaded France and just absolutely smashed the French. They surrounded Paris and then they took the [00:32:00] capital. So one of the famous things that came out of this war is that the French used pigeons to relay information to other captured cities.

Um, but the way that they would do it is really cool. It's, it's a step above just writing something on a parchment and then sending that somewhere else. So what they would do is they would put documents, pictures, whatever dispatches, they would shrink it down to microfilm size, like put it on a really, really thin sheet of whatever.

They would roll that up, put that on the pigeon, they were able to get a ton of data on this thing. The pigeon would fly to wherever it's going. The people on the other end would take this microfilm, unravel it, stick it in front of a lantern, then blow the image up. They were able to see dozens of pages of documents and photos, and this is back in 1870.

How cool is that?

Cameron: Yeah, I didn't even know they had that capability in 1870. They're essentially just reducing a briefcase down to this little tiny sheet that could be [00:33:00] attached to a pigeon. That's really cool.

Cory: I know it sounds like a cold war maneuver.

Cameron: Yeah, exactly.

Cory: Uh, pigeons had extensive use in the world wars.

This isn't the age of aircraft, but it makes sense to use pigeons. They're not easy to shoot down. They don't suffer mechanical errors. On a government scale, they're not expensive to train and to put in the field. One article from the Evening Star in 1941, and I love the name of the article, it's "Birds Against Hitler".

Uh, it highlights a story where these beleaguered soldiers, they, they were in a situation where all of their radio equipment was blown out and they had no way of contacting anybody. So they sent their pigeons off to deliver an important message to headquarters. And then 20 minutes later, after they release it, it arrives.

Cameron: You can be a pigeon on the right side of history against Hitler, or you can be some crappy little bird like a seagull who was probably for Hitler. [00:34:00]

Cory: There were a lot of pigeons used in both world wars. By the time World War II ended, great Britain had 750,000 pigeons in its service. The German army actually did use pigeons, and what they would do is they would strap little cameras to the chest of the pigeons and then have them fly over whatever topography and, and, and capture cities, lakes, troop movements.

Whatever it is. They, the, the Royal Air Force, the RAF actually had a pretty clever system in place where to collect information and data about the Germans they would just drop caged pigeons over towns, allied troops, whatever. Um, and the cage would have instructions like, fill out this questionnaire. Have you seen any Germans? How many Germans have you seen? Where are they going? You fill it out, you attach it to the pigeon, you let it go, and then it'll fly back to home base, wherever that is. The public and the military loved their pigeons. If you search newspapers from World [00:35:00] War I and World War II that talk about pigeons, they just gush with their appreciation and their love for these heroes that are, you know, relaying critical information and, and saving lives.

Here's a story from a 1918 article titled Homing "Pigeons Aid Pershing". Pershing was the commander of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I. During December, a patrol boat released a pigeon as it was torpedoed by a German submarine. The crew was floundering in the water and clinging to wreckage.

The German saw the bird and wounded it with a rifle shot. It was not brought down however, and 12 miles away landed on the deck of another patrol boat with five flight feathers missing. The bird knew it could not have reached land and sought this place of safety. The message the pigeon bore gave the location of the wrecked patrol boat and the captain of the vessel on which it landed, succeeded in reaching the spot in time to save every man.

Cameron: This is almost like a Lassie kind of story.

Cory: Uh, one of the [00:36:00] most famous war pigeons is named Cher Ami. It was a pigeon during World War I. The story goes that in 1918, an American regiment commanded by Major Charles Whittlesey became separated from the front line. They found themselves in a terrible position as they were trapped between a German offensive and their own American allies. So the Americans on the front line start to bomb the Germans, but they didn't know that their regiment was where the Germans were as well. Whittlesey's men are being killed around him. There would ultimately be 30 men killed by this friendly fire. Um, and he's sending out pigeons to the Americans to ask that they stop firing.

The Germans saw that Whittlesey was sending out pigeons and they kept shooting the pigeons out of the sky so that the messages couldn't be delivered. Whittlesey took his very last pigeon that he had, Cher [00:37:00] Ami, and attached a note to it that said, "we are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us, for heaven's sake stop it." So they release Cher Ami, it takes up in the air and it's immediately shot down. Its leg is blown off, but she gets up again, just dodging bullets along the way. She makes it through and she lands at the American frontline and delivers the message, uh, and probably saved the entire regiment from being destroyed throughout the war.

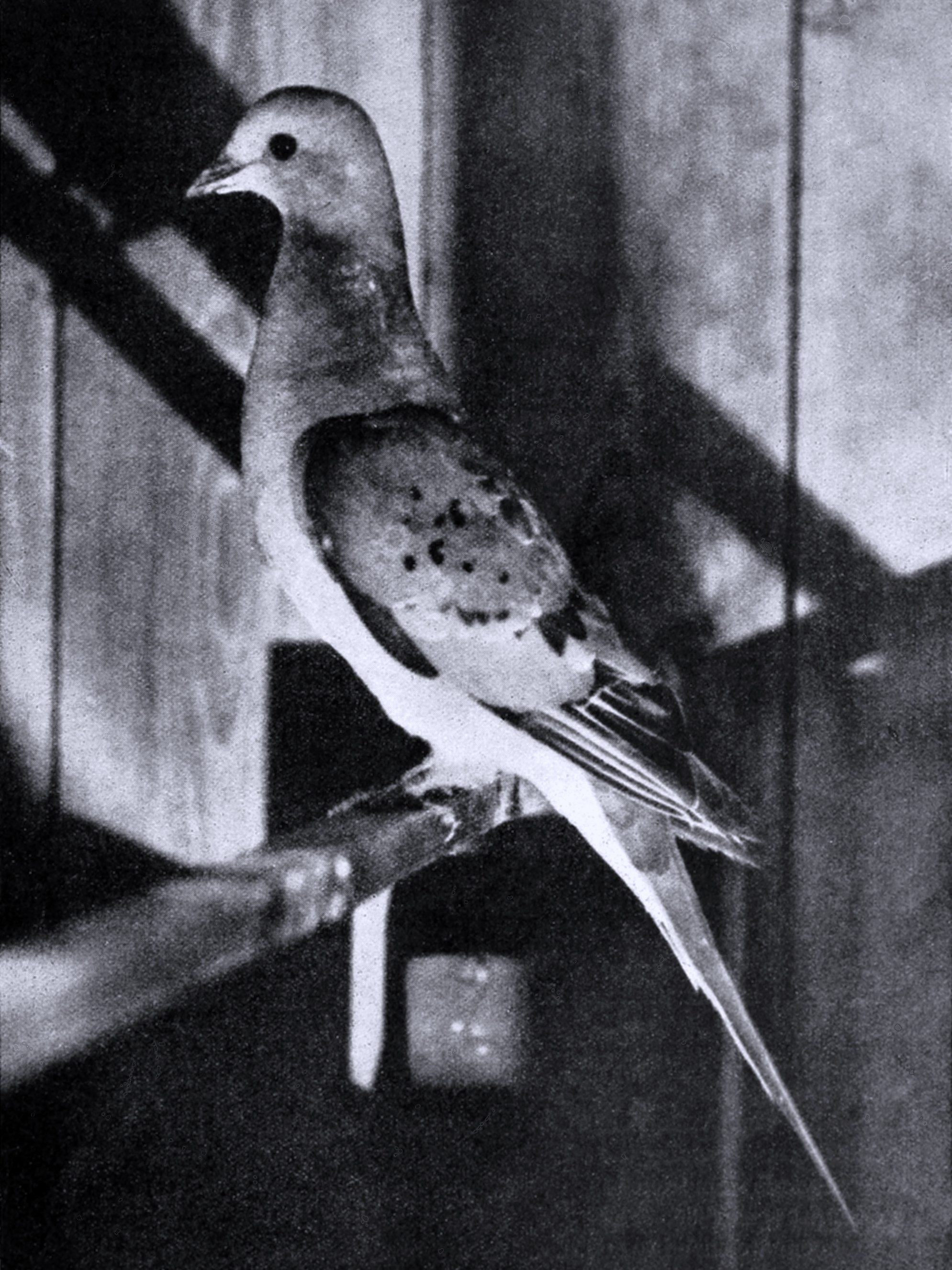

Pigeons were heavily decorated and honored for their work, and Cher Ami is actually on display at the Smithsonian today.

Cameron: Wow, that's really cool. You know what, I'm a big fan of pigeons. I, I like what they're doing. I take back everything I said about rats with wings.

Cory: Well, Cameron, welcome brother. But unfortunately, the story about the pigeons is going to take a bit of a sad turn here after World War II, the relationship.

Between humans and pigeons suddenly [00:38:00] begins to sour and that animosity begins to build up, and it leads us into where we are today where people just don't like pigeons. But before we get into that, one little side note here, I I, I do want to talk about passenger pigeons. The reason that we haven't really talked about them yet is they are not rock doves.

They are a totally different species of pigeon. They are not domesticated. They aren't related to feral pigeons today, or these homing pigeons or the fancy pigeons that we've talked about. They're their own entirely different species. But Cameron, you looked into passenger pigeons a little bit and I was hoping you could answer a couple of questions.

Like, I know that they are extinct. I don't know why they are extinct. Um, I know that there used to be a lot of them and they're gone.

Cameron: Yeah, it, it always kind of astounded me because I read these stories from, you know, the late 1800s, early 1900s, where passenger [00:39:00] pigeons were so abundant that they could just block out all the light from the sky.

There would just be like billions flying overhead, and it would leave a town below just covered in pigeon poop. Just be completely white. Um, so I couldn't understand how an animal so abundant could just go completely extinct. And part of it had to do with the fact that scientists have noted that their population just naturally goes through booms and busts.

And it's part of their evolutionary trait, which is called, uh, predatory satiation, which it, uh just speaks to itself kind of. It's that there's so many of them predators can only eat so much, so you just kind of, it's a numbers game for survival. If there's enough of these pigeons, they'll survive all these [00:40:00] predators.

Cory: That, that's like how cicadas work too, right?

Cameron: Exactly. Yeah. And the problem is humans started hunting them. So, you know, they were set up, evolutionarily speaking, to work with their existing predators where there was enough of them to go around and they could, uh, quickly reproduce. But once humans started hunting them, they were already going in between their boom, back into a bust, and all of a sudden there weren't enough pigeons for this, uh, strategy to work.

So humans started killing them off too quickly. Their predators started killing them at an abundant rate, and it was only a matter of time before it would, that would be the end of the passenger pigeon. Okay. So if around the beginning of the 20th century, end of the 19th century, we had so [00:41:00] many domesticated pigeons and people kept them as pets.

How did we get to the point where cities are just overrun with feral pigeons and nobody has them anymore?

Cory: One of the big reasons to have a pigeon was because of its homing ability, and once new technologies were developed, the homing pigeon, its ability became sort of obsolete. I, I would guess after World War II, like there were so many pigeons because of the wars, but governments didn't really need them anymore.

People fell out of interest with the hobby, maybe because they had TV now and, and you know, unlike a dog or a cat, if you release it, you know, it might or might not live. Pigeons thrive not being inside of a house or being in a coop and they are totally fine replicating themselves and enjoying themselves in, in a city street.

So. So like not only were cities just great [00:42:00] places for pigeons to find a place to live like on skyscrapers and bridges and whatnot, it replicated their native habitat. But pigeons also have kind of a unique ability amongst birds, where like a lot of birds need to have seeds and nuts and berries. Rock doves can kind of eat whatever.

They can eat garbage and the way that they feed their young is they actually turn all of this stuff into kind of a milky substance and then they regurgitate that into their kids. So it doesn't really matter what food is available because they can just process that food and are able to nourish chicks.

So, once pigeons were out in the wild, they still hung, I'm sorry, once pigeons were out in cities, they're still hanging around humans. They're still doing things that they've always been doing for thousands of years, but just the conditions in cities made them so successful. By about the [00:43:00] 1960s people and the press started to notice that there was a pigeon problem.

People were getting upset with the huge population of pigeons in cities and all of the droppings. Papers were reporting that pigeon droppings were killing people, which was not at all substantiated. Like that's not true. And then there became like a new generation of humans that had only ever seen rock doves living in cities.

I read one article that really credited Woody Allen's 1980s film "Stardust Memories" for Coining, a phrase which basically sticks in the mind of everybody when they think of a pigeon. Do you know what that phrase is?

Cameron: No. I'm, I'm not a Woody Allen fan.

Cory: You used it earlier today.

Cameron: Oh, is this rat with wings?

Cory: Rats with wings.

Cameron: I didn't know that that was Woody Allen. That's disappointing.

Cory: Cities today have to try to figure out how to [00:44:00] control their pigeons. And there's a bunch of different ways to do it. Um, they can, they, they can try and get people to not feed pigeons. Some people try to exterminate them with poisons, but, I mean, but that, but that's like an impossible task.

There's just so many pigeons and they're just so easily able to procreate. I read that Melbourne had had a pretty interesting solution. In 2015, they built this huge $70,000 metal coop that was designed to replicate like what rock doves like to see like a bunch of alcoves and, and basically what their plan was there is that the pigeons would go inside of this, this gigantic structure, and then workers would go in and remove the eggs to try and drop the population down.

The pigeons never took to it, because, this is quoting from the article, "the nature of the pigeon is that they find a home and they stick with it. So finding them somewhere else to go is a bit of a dream. Ultimately, pigeons are just too closely linked to human society. [00:45:00] Their success was based on human habits."

So if you're going to have them live in a human environment, you're not going to ever remove the thing that made them so successful in the first place.

Cameron: They're with us till the end of humanity, I'm assuming, at this point.

Cory: I saw a pigeon in the parking lot and it was like I hadn't seen a pigeon since doing all of the research for this, and then I just saw it and I was just like, Hey, little buddy.

I know your story.

Cameron: Well, thanks for giving me a different perspective on pigeons because I, I won't lie, I've always seen them. As a nuisance whenever I'm in a big city, but I think this has given me, given me a newfound appreciation for pigeons.

Cory: So, Cameron, when I say dove, what do you think?

Cameron: I think pigeon.

Cory: That's a good place to end it.

Cameron: Well, thanks again. Uh, we will be posting some pictures, some links on our website [00:46:00] lostthreads.org and we'll catch you next time.

You can find more pictures of fancy pigeons at the American Pigeon Museum