Public Access TV vs. The First Amendment

The proliferation of cable TV led to the inception of public access channels - a place where regular citizens were given resources and airtime with the full protections of the first amendment. Without editorial control, the community responded to objectionable speech in a number of ways.

The Great Satan At-Large

Lou Perfidio's "The Great Satan At-Large" was a response to the extremist evangelical content being broadcast on cable television. But Tucson residents weren't happy to see equally extremist and inflammatory content delivered by Satan.

The community responded by flooding the local public access station with complaints, which resulted in the show's temporary removal while the city attorney pursued obscenity charges. Perfidio argued that the show was performance art protected by the first amendment. Additionally, his show featured content that was already being aired on public access and cable—though admittedly not in such a concentrated dose.

Episodes of The Great Satan At-Large, along with news broadcasts about the show and John C. Scott's interview with Perfidio, are available on the Internet Archive.

Bonus: Here's a video of Lou Perfidio teaching Bryant Gumbel how to play pinball on The Today Show in 1990.

Dirge for the Charlatans

"Dirge for the Charlatans" was a public access television show broadcasted from Briarcliff Manor, New York. On the program, host Clay Tiffany aired his grievances about public officials and the police. This incessant nitpicking put him on the radar of many public officials who worked to silence him.

The library board felt uncomfortable with Tiffany's use of the building to tape his "anti-Briarcliff show," and they ended up restricting the use of the library for everyone in the community.

After local cop Nicholas Tartaglione brutally beat Clay Tiffany for speaking about him on his public access TV show, the Briarcliff Manor police and district attorney Jeanine Pirro refused to investigate. At this point, the FBI would get involved.

Dirge for the Charlatans Episode 53 is available on YouTube.

Community Responses

Tom Metzger, neo-Nazi and former grand dragon of the Ku-Klux Klan, saw public access television's free speech protections as an opportunity. He taped episodes of a racist show named "Race & Reason" that were distributed to white supremacists around the US and aired on their local public access stations.

In our episode, we speak more about the community responses to this content and how it could be applied to issues around hate speech under the first amendment today.

Sources:

- 1978 KGUN news broadcast about cable TV entering the Tucson area (University of Arizona Library).

- Bigotry and Cable TV: Legal Issues and Community Responses (1988)

- Supreme Court decision in Manhattan Community Access Corp v. Halleck (pdf)

Episode Transcript

Cameron: The last few decades of the 20th century were a golden era for public access television. Like an early version of YouTube, these programs were created by the community, for the community, and were often fun and bizarre glimpses into the minds of your neighbors. Today, social media has taken over the role that public access television once held. Platforms like TikTok, X, and Instagram are now the main way we communicate our ideas.

A major difference between the two is that social media curates what we consume through an algorithm. Content that's trending, paid, or proven to be to your taste, gets elevated to the top of your feed.

And for better or worse, controversial and unpopular speech that doesn't align with the values of the platform may be suppressed or removed completely. Public access television was the complete opposite, where shows were granted the full protections of the First Amendment with no government or corporate editorial control.

That meant if you had an idea for a show, you could tape it and broadcast it to your entire community with virtually no barriers. However, given such free reign for self-expression, some of the programs inevitably delved into unpopular or even hateful speech. Those extreme cases would test the limits of public access television's First Amendment protections, and communities were forced to grapple with unpopular speech in a landscape where moderators didn't exist.

Cory: In today's episode of Lost Threads, we're going back to the era of public access television and looking at stories where free speech limits were tested and how different communities responded to content they disagreed with.

Cameron: I'm Cameron Ezell.

Cory: And I'm Cory Munson. We'll be right back.

So, Cameron, one of the things you mentioned in the introduction is that public access television enjoyed complete First Amendment protections. But before we jump into our story, let's talk about how this would have never happened without the invention of cable television.

Cory: When TV first took off in the US you could only get a picture if you could pick up a signal from a broadcast tower. Back then, rural communities or really anyone living between a tower and any obstruction like a mountain or even a tree, couldn't receive a picture. That was unlucky for them because TV was quickly becoming the most important way to get any news or entertainment. But a tree was not going to stop our elders from entering the modern era. An early solution was to build a giant antenna on top of a mountain and then run a really long cable down to the community. This was cable TV version 1.0 and soon every town in the US wanted it.

Cameron: That sounds like something that only happened in rural towns away from the broadcast towers. So early on, cable wasn't really intended for cities.

Cory: Right. And the FCC actually had rules in place that prevented cable operators from moving into urban areas. They wanted to keep this new disruptive technology out of their top 100 markets. And that was just to protect local affiliates who were using broadcast towers.

But as demand grew, the FCC started to relax those rules. And starting in the 1970s, cable TV began to expand into cities across the US. But there was a problem. It took significant work to build this cable infrastructure- think digging up roads, running tons of cable lines across town. And because infrastructure was so limited, only a single franchise would have the right to operate that city's network.

That meant that if a cable company could win the license to serve a major city like Los Angeles, they would enjoy virtually zero competition in the cable TV space. Effectively, it'd have a monopoly.

Cameron: That's interesting and a little annoying. I've always been pissed that when I go to sign up for the internet, or you know, in the past cable tv, there's only one company to choose from, like Cox or Charter, and it always ends up being an awful experience. There's no other options. So you're saying the government actually created these monopolies.

Cory: Exactly. And the FCC even acknowledged it was creating monopolies. So to correct for this market control it had a very specific, somewhat strange requirement if these companies wanted to keep their license.

The FCC mandated that cable companies must set aside public access channels and they had to provide broadcasting equipment for the community.

And the public access channels were only one part of the FCCs requirements. They also mandated that cable operators would have zero editorial control over any content produced by the public. As long as the content was not commercial in nature, public access cable would enjoy absolute and unrestricted free speech.

And free speech meant just that; profanity, sexual content, nudity, religious preachings, or even hateful, racist rhetoric were all fair game as long as it fell under the purview of the First Amendment.

Cameron: And this is different from over the Air Network TV, right? The whole Janet Jackson Super Bowl halftime show led to tons of complaints and fines and SNL gets in trouble if profanity goes out on live tv, for example.

Cory: Exactly. It almost seems a little backwards, but free speech guarantees don't extend to radio and airwaves owned by the public. Those are highly regulated for content. Cable TV wasn't regulated because it's a private subscription service.

Cameron: Why do public airwaves have so many restrictions on what you can say? Because I would think that's where First Amendment protections would be strongest, since the federal government has more oversight.

Cory: Well, over the past few decades, the public has made it pretty clear that they don't want to hear or see explicit content on public airwaves. They've complained enough times. And the FCC has been forced to step in and act as a custodian, i.e regulate content, to serve the public good because that's what the public said they wanted.

In the late 1970s, the FCC started letting cable companies into the top 100 markets. Tucson, Arizona was one of those cities. Now, remember, only one provider would be granted the franchise to operate in Tucson. So cable companies had to outdo one another to attract the city's favor and earn the license. They did this by offering services that the community would enjoy. Here's Tom Volgy, then city Council member and future Tucson mayor, speaking to the local news in 1978 as the city was vetting (clip of Tom Volgy from news broadcast) cable companies.

Ultimately the Tucson license would go to your favorite internet provider, Cameron: Cox Communications.

Cameron: I have beef with Cox, as I'm sure a lot of people do.

Cory: Well, maybe back then they weren't so bad because Cox agreed to work closely with the community to create public access programming, including providing facilities the public could use to create their own shows.

And as public access came online in Tucson a whole spectrum of human expression and content followed. Think early days of the internet.

Along with all that weird personal content came the inevitable, hateful and extremist stuff. But remember, per the FCC requirements, as long as it didn't violate the first amendment, that was all protected speech and it was allowed to air.

In this brand new public forum where anything goes and cable companies couldn't even exert editorial control, content regulation was left entirely to the public .

Tucson's new public access television gave the community a new way to express itself. It also attracted divisive content, which neither the government nor the cable companies had any authority to control.

Cameron: In response, one Tucson resident created a show that would test what the community was willing to tolerate.

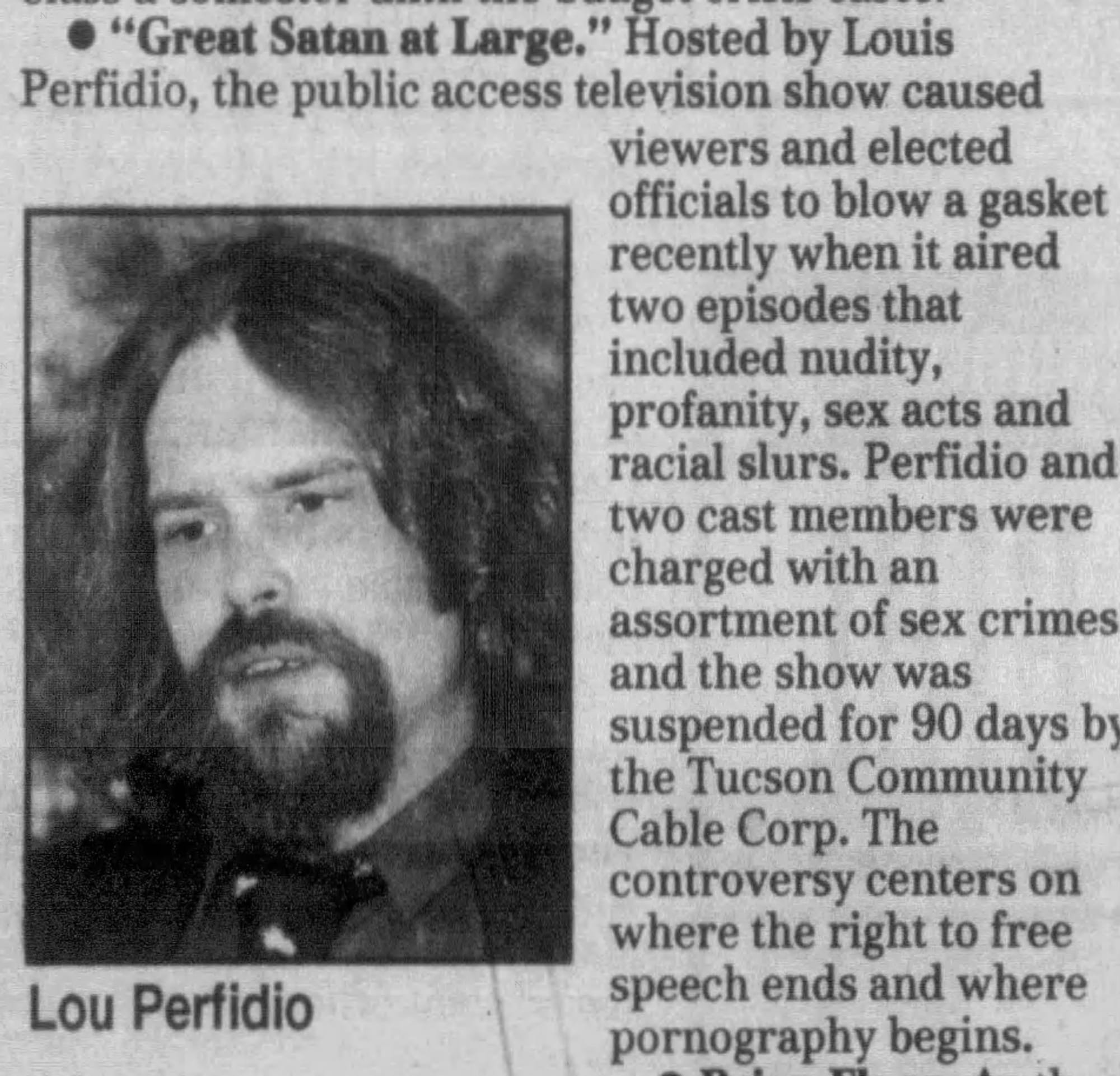

Lou Perfidio had worked as a writer for the Philadelphia Enquirer and moved to Tucson following the loss of a job, girlfriend, apartment, and his pet cat. This isn't super relevant, but I thought you might find it interesting, Cory, that before he moved to Tucson, he considered himself to be the king of New York pinball and the New York Times even did a whole writeup on him.

Cory: I love pinball, but what made him the king?

Cameron: He made it a point to get high scores on all of the machines in bars across soho, but there was also an elusive mystery player that went by ZIF Z-I-F on the high scores that Lou was desperately trying to track down. Did he ever find ZIF?

Unfortunately, ZIF remained elusive, but he did have a segment on the Today Show where he taught Bryant Gumbel how to play.

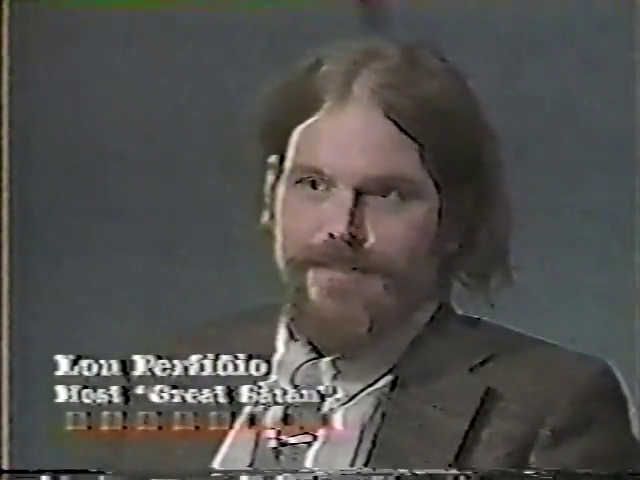

So Lou moved to Arizona and started encountering extreme evangelical and right wing content on Tucson's local public access station known as TCCC. Perfidio was not a fan of the extremist broadcasts on public access and decided he would make his own satirical show in protest. That program was called The Great Satan At-Large.

(clips from show)

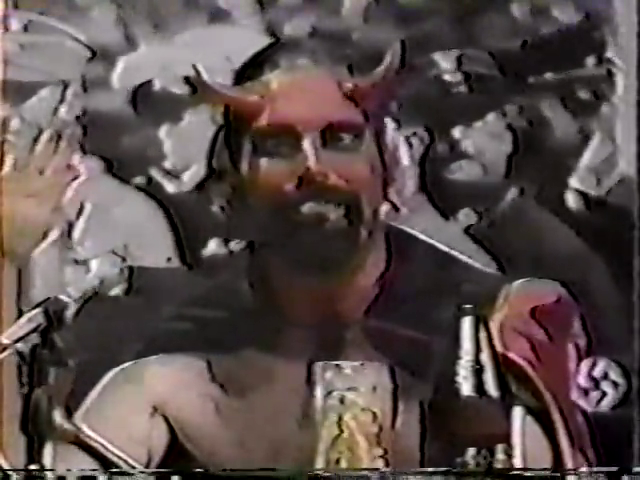

Cameron: The Great Satan At-Large featured Perfidio as a cartoonish version of Satan, complete with red makeup and a plastic pitchfork, acting as the host of a chaotic and crude late night call-in show.

His co-host was a drunk jester that masturbated throughout the show, and the green screen behind Satan featured things like Hitler at a rally, or a young woman groped live in the studio by a masked man called the Sexecutioner. The desk that Satan sat behind was covered by an American flag with a swastika painted across it.

Cory: Classy.

Cameron: I'm the furthest thing from a prude, and even I have a tough time watching the program.

It's filled with sexually explicit material and language, racial slurs, expletives, and even the Tucson locals who called into the show piled on.

But from Perfidio's point of view, he wasn't doing anything other shows weren't doing. Yeah, he was crude and lacked any sort of subtlety, but even though it was divisive, it was still protected speech. And at least the great Satan was open about what it was doing. The programs he was protesting camouflaged themselves as boring talk shows or religious sermons.

Cory: I have to imagine that The Great Satan At-Large got a lot more pushback from the community compared to the evangelical stuff.

Cameron: Oh, a hundred percent. TCCC received a flood of angry calls and letters demanding the show be taken off the air, but, and I think this is pretty cool, Tucson's then Mayor Tom Volgy stood up for the great Satan and reminded the city council that they had no editorial control over the content.

Following the outrage, John C. Scott, a local TV and radio personality, interviewed the executive director of TCCC, who echoed the mayor's position.

(clip from broadcast)

Cameron: During the show, John C. Scott took calls and recorded a live vote to see what the public sentiment was in regards to the great Satan at large. And although there were a few citizens concerned about the content, most of the callers seem to agree that censorship of any form should not be allowed.

The live vote would end with 54% of viewers agreeing there shouldn't be any content standards applied to public access television.

Cory: I wonder if more people would've supported the show if it was still overtly adult content, but played it to their expectations of what protest art was supposed to be like, a nude ballet.

Cameron: Yeah, I think presentation is pretty important. If you have a talk show where people sit in boring suits, presenting carefully delivered hate speech, many people won't see the issue. But when Satan delivers the message alongside a masturbating jester, suddenly it becomes a problem.

Cory: It's like how AI can say the most inane thing, but it's hidden behind perfect grammar. So people just think it's well-reasoned.

Cameron: And you mentioned a nude ballet earlier. I really think that what Lou Perfidio was doing was in the same category of strange performance art, and it made people uncomfortable and challenged them, which, you know, I guess is what art is supposed to do.

I definitely don't endorse any of the messaging from his show or from the televangelists, but if you're gonna give a platform to one and not the other, then it's clear that free speech only extends to certain groups.

Cameron: In an effort to address some of the blowback, TCCC looked for solutions that did not involve censorship. They considered moving the show to a later time slot to limit the number of younger viewers who might see it.

Another solution offered was to label Great Satan as adult programming, which meant it would air scrambled and if customers wanted to watch it, they'd need to opt in to receive the unscrambled broadcasts. Additionally, the city attorney threatened legal action against Lou Perfidio for various obscenity charges with a possible sentence of up to 20 years in prison.

Perfidio had planned on challenging the charges until it was discovered that one of the people being groped on his show happened to be a 17-year-old girl.

Cory: Well, that's a good way to kill your message.

Cameron: Yeah, not great. This would result in multiple members of the show to be charged with contributing to the delinquency of a minor and receiving unsupervised probation, ending the show after only two episodes.

Following The Great Satan's removal from Tucson Public Access, Perfidio would go on to lead a quiet life as a cab driver and freelance writer. On his blog titled, "I Love Misery", he continued being foulmouthed and cynical, especially about Phillies baseball. Lou Perfidio died from MRSA in 2006 at the age of 43.

The Great Satan At-Large never had its showdown with the city over its first amendment rights, so we'll never know how this would've played out. But this was not the only time a community fought back against a public access show they disagreed with.

Cory: Earlier we talked about how public access television introduced a new age of self-expression. Suddenly, everyday people had access to creating a program themed around whatever interested them, like music or comedy. But many also used this public forum to express a deeply held conviction like Lou Perfidio, who created The Great Satan At-Large to protest obscene and inflammatory programming.

Some people, on the other hand, used public access to fight the system itself and call out local officials for corruption.

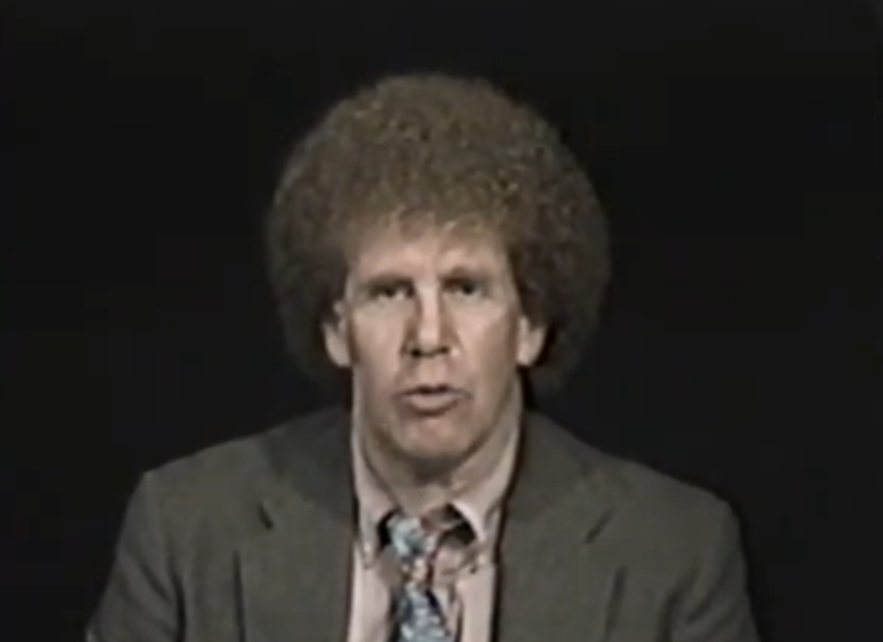

Clay Tiffany was a longtime resident of Briarcliff Manor, a small village north of New York City in Westchester County. A tall athletic man with an unmistakable head of curly red hair, Tiffany described himself as a journalist. But others in the community would label him as an annoyance. That was probably because they were tuning into Tiffany's public access show, Dirge for the Charlatans, which began taping in 1995.

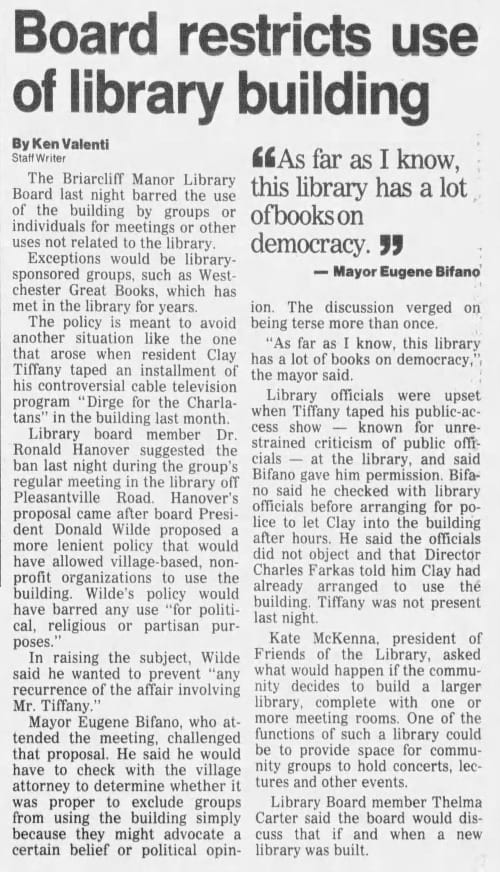

in his show, Tiffany spoke straight to the camera in front of a static background, rattling off the names of local officials he perceived as corrupt. The show was originally shot in a room at his local library, but the library board became uncomfortable with the content. They deemed it "anti-Briarcliff" and they fought to keep Tiffany from taping the show there. But the mayor of Briarcliff Manor, Eugene Bifano, stood up for Tiffany's right to free speech and he urged the board to continue to let him shoot in the library. In the end, the board created a general rule that barred any meetings not directly related to the library.

Cameron: So high school tutoring, tax advice services . That was all out.

Cory: Yeah, the rule change was clearly targeted at Tiffany.

Cameron: It's interesting that in both stories, it's the local mayor standing up for free speech on public access, and I do appreciate the fact that this mayor actually went to bat for Clay because I'm sure he wasn't a fan of his messaging.

Cory: Yeah. And aside from a few judges that ruled in Tiffany's favor later on, Mayor Bifano seems to be one of the few public officials that actually stood up for him. Now, the library was not the first time Tiffany had been barred from public spaces in Briarcliff Manor. Two years earlier, in 1993, village Manager Lynn McCrum signed an order that banned him from visiting Village Hall saying he would stay for a long time and pester the staff.

Cameron: There's a whole group of individuals today that I see on social media called First Amendment Auditors, and it sounds like he was an early version of them. And what they do is basically go to a public government building, like City Hall or the post office or a library, and take video because it's their right to do so.

But most of the time they're just looking for a reaction from public officials that they can take advantage of.

Cory: Exactly. We're not making the argument that Tiffany wasn't super annoying, but overall, the ban ended up working in his favor because the Westchester Civil Liberties Union took up his case and he ended up winning $85,000 from the village.

Back to Dirge for the Charlatans, since Tiffany was now unable to tape his show at the library, he set up a studio in his apartment, and that's where he spent the next half decade crusading against local officials and corrupt police. But unfortunately for him, the claims he made on his public access show would soon have real world consequences.

In 1997, Clay Tiffany was arrested after he showed up to a police station requesting a copy of a report he had filed. Now, the police claimed Tiffany continued to harass them even after they gave him a copy of the report. However, during the arrest, Tiffany was carrying an audio recorder that refuted the statements made by police and the charges were dropped.

Despite the fact that police were caught in a lie, Village Manager McCrum, took their side calling Tiffany a nuisance. But this was only the start of Tiffany's problems with the Briarcliff police. The year before this arrest, the Village police had hired an officer by the name of Nicholas Tartaglione. He began tuning into Dirge for the Charlatans and became completely outraged by the show's endless criticism of the Briarcliff Police.

This led to Tartaglione pulling Tiffany over to threaten him, saying he had mob connections and could take care of him anytime he wanted. Obviously this freaked Tiffany out, but when he tried to flag a driver for assistance, Tartaglione slammed him against his car and arrested him.

After he was released, Tiffany went on his show to call out the police brutality, but he was ignored by public officials, including Westchester County District Attorney Jeanine Pirro, who's now US Attorney for the District of Columbia.

Cameron: Cory, I know I've told you this, but I can't stand Jeanine Pirro. As you just mentioned, Trump appointed her as the US attorney for DC and she's also a Fox News personality. Most recently, she was bragging about bringing charges against a protester who threw a sandwich at a cop, and she lost. Nearly every single case she's brought before a grand jury this year has failed to get any indictment.

Cory: Well, it's said you could get a grand jury to indict a ham sandwich, so that was a terrible case for her to lose. Tiffany also despised her. There's actually a really funny story that came up in my research. In 2003, Jeanine Pirro was at a Barnes and Noble for a book signing, and he showed up to heckle her. Pirro definitely knew who he was, so she just smiled and sarcastically said, "Hey, it's good to see you". And he responded with, "what's the matter, Jeanine, did you have a bad facelift?"

Cameron: My favorite part of this story is when her bodyguard and the store security started to escort him out of the store and he started yelling, "I have a Barnes and Noble card, and I'm not being allowed to stay in that part of the store!".

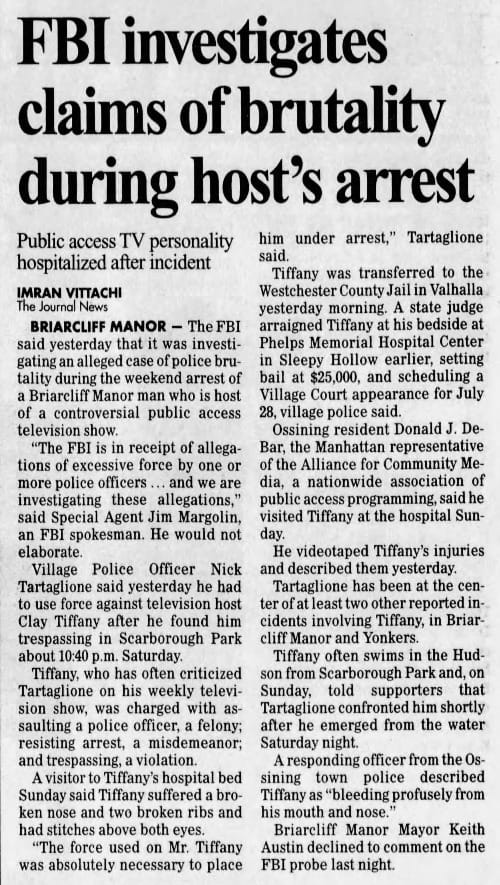

Cory: So for the next few years, the cycle repeated: Tartaglione privately brutalized Tiffany, and Tiffany publicly called out the harassment. But in 1999, Tartaglione reached a breaking point. Now, Tiffany was known to swim in the Hudson River from a park in Briarcliff. One evening, as he was leaving the park to head home, he was approached by Tartaglione. The officer yelled, "stop talking about me on your TV show!", And proceeded to beat Tiffany so badly that he ended up in the hospital with a broken orbital, a broken nose, and multiple broken ribs.

Cameron: How did they even try to justify that afterwards?

Cory: It was pretty weak. Tartaglione said Tiffany had been trespassing at the park after it closed and resisted arrest. And police and local officials took Tartaglione's side. Tiffany recorded his next episode of Dirge for the Charlatans from his hospital bed. He once again exposed Tartaglione's brutality, all while bruised and wrapped in bandages. After a few days in the hospital, Tiffany was transferred to a jail cell for the charge of resisting arrest.

Cameron: It's really frustrating to hear about all of this harassment. I can't imagine what it was like for him to have all of these injustices videotaped, audio recorded, documented in the paper, and nothing happens. Nothing comes out of it. The cops continue to harass him, beat him, and the government just files charges against him for speaking his mind on tv.

Cory: Well, there's finally some good news for Tiffany. Despite the fact that local officials refused to do anything about Tartaglione, the FBI decided to open their own investigation. Soon after the FBI entered the scene, district Attorney Jeanine Pirro quietly dropped the trespassing charges against Tiffany, but she still refused to investigate any of the claims made against the local police.

So in response, Tiffany began filing lawsuits against both the police and Nicholas Tartaglione. After three long years, Tiffany achieved a major win in both his suits. He was awarded $900,000 in the case against the village and another $200,000 in his case against Tartaglione.

Interestingly, Briarcliff's insurance paid Tiffany for both cases, absolving Tartaglione of any responsibility.

Cameron: Wait, wait. So Briarcliff's municipal insurance paid out the money in the case against the city. That makes sense. But it also paid out in the case directly against Tartaglione?

Cory: Yep. And even worse, not only was Tartaglione reinstated to the Briarcliff police, he was awarded $300,000 in back pay, which is $100k more than Tiffany received for getting beat up by the guy.

Cameron: He was reinstated? So he was let go for beating Tiffany and then got his job back?

Cory: No. Tartaglione wasn't let go from the police for beating Tiffany. In a confusing turn of events, he was fired a few years earlier for something totally unrelated to this case.

He was charged with perjury and was let go from the police force. But he was later found not guilty, so he sued saying he shouldn't have lost his job for a crime he didn't get charged for.

Cameron: And he made $300,000 for it. So why would the village insurance pay out in Tiffany's case against Tartaglione?

Cory: So, Clay Tiffany's attorney Joanna Schwartz, wrote a book called Shielded where she talks about this case and mechanisms that protect police officers. It all comes down to what's called indemnification laws. Basically, if a professional, like a truck driver or a doctor is operating in good faith while doing their job, they can't be held personally liable.

Cameron: Yeah, that makes sense. But obviously Tartaglione wasn't operating within the scope of his employment. This was a personal grudge he held and beat this innocent man while he was on duty.

Cory: But if the insurance companies hadn't settled on Tartaglione's behalf, he would have sued them for violating those indemnity laws. Then the insurance would be looking at yet another lawsuit. Paying for Tartaglione's bad behavior was a cost saving measure.

Cameron: So like most things, it sounds like it just comes down to the bottom line. So after all of this, did Tiffany continue with his show?

Cory: By the time Tiffany won his court case in 2004, he had already ended Dirge for the Charlatans. And there's not too much to say about his retirement years. He went to live a quiet, isolated life in the nearby village of Ossining, and he passed away in 2015 from natural causes at the age of 68.

Cameron: At the very least, he was compensated . But I can't believe someone like Tartaglione got to continue being an officer.

Cory: Oh, we're not done with Nicholas Tartaglione. He'd end up making national headlines in 2016.

By 2016, Tartaglione had graduated to a full-time drug dealer. What happened is he believed that a man named Martin Luna had stolen money from him, so he invited Luna to meet up. Luna didn't suspect anything and brought his nephews and a family friend to the meeting, but it was a trap. Tartaglione tortured Luna before strangling him with a zip tie. The other three had been forced to watch, so they were witnesses. After he murdered Luna, Tartaglione took them out to a remote area and executed them.

He was sentenced to life in prison where he shared a cell with a man named Jeffrey Epstein.

Cameron: This all circles back to Epstein.

Cory: Yes. Three weeks before he was discovered dead in his cell, Epstein was found barely conscious in what authorities determined to be a suicide attempt.

Epstein maintained that he did not attempt suicide. He said it was Tartaglione who attacked him.

and who paid Tartaglione to carry out this hit? Well, I think you have to only look at who benefits, and to me, the obvious suspect is

Cory: Clay Tiffany and Lou Pio are both good examples of how Public Access television presented many challenges for their communities.

People, understandably, would rather avoid hearing hateful, offensive, or disagreeable speech when they turn on their TVs, but deciding which content should be made available and which should be censored is dangerous territory. Companies like Disney or X are free to create their own guidelines and moderate content at will. But public access television's community guideline was the first amendment. That's challenging to moderate. And outside of methods we've seen in this episode, like legal threats or outright violence, many communities had to learn how to address issues with free speech in a way that didn't infringe on the rights of citizens.

Cameron: In the mid 1980s, Tom Metzger, the head of the White Aryan Resistance, and a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was producing episodes of a show called Race and Reason. After making the show, he'd send episode tapes to white nationalists around the country. In turn, they'd request time on their local public access channel to broadcast the racist content.

In the fall of 1986, an extremist white nationalist group called The Arm of God petitioned Pocatello, Idaho's Channel 12 to air Race and Reason. Residents became concerned this programming would serve to enlist community members to the group's cause. But instead of trying to shut down or censor the show, which would've certainly led to years of legal battles and attention for the KKK, Pocatello's Channel 12 aired the program just like any other content that came their way.

Their strategy was to instead focus on public education and counterprogramming. The station teamed up with a Pocatello based human rights council for a 16 month campaign to create shows tailored to address the inflammatory content. Before an episode of Race and Reason aired, it was reviewed by a committee for misinformation. Then in the time slots directly after the broadcast, they showed counterprogramming that addressed the conspiracies and hateful content propagated on the show.

From what we could find, the community overwhelmingly supported this approach. Race and Reason ended up fizzling out after its scheduled 36 episode run.

Cameron: In the late 1980s, the National Institute Against Prejudice and Violence published a paper that evaluated how communities across the US addressed bigoted programming on public access tv. Most adopted one of three strategies.

The first was to legally challenge the content, which is an uphill battle that nearly always ends with bad actors not only winning in court, but receiving more attention.

The second strategy was to remove the public access channel entirely. This prevents the airing of hateful or disagreeable content, but it also deprives the community of a public good.

The third was to focus on counter programming and education. As in the case of Pocatello's response to Race and Reason, that strategy was and continues to be one of the most effective ways to combat hate speech.

Cory: Today, public access television has largely disappeared. Obviously, part of that is because of major shifts in how we consume media. Places like YouTube and TikTok are the new public squares. But it's not just the medium that's disappearing.

The public access era of unconstrained self-expression is also over, and it will probably never happen again. One reason for this is because new laws and rulings have worked to strip public access of its First Amendment protections.

In 2019, the Supreme Court took up Manhattan Community Access Corp v Halleck. In this case, a woman named DeeDee Halleck hosted a public access show where she was critical of the community's public access station after not being allowed to film one of their board meetings. The network responded by canceling her show. The conservative majority in the Supreme Court ruled that free speech protections should not extend to media entities owned by private businesses. This ruling effectively terminated the First Amendment protections that public access television had enjoyed since its inception. In his first Supreme Court case following his confirmation, Justice Kavanaugh wrote for the majority opinion:

" Grocery stores put up community bulletin boards. Comedy clubs host open mic nights... merely hosting speech by others... does not alone transform private entities into state actors subject to First Amendment constraints."

Cameron: What he's saying here is that a comedy club has the right to cut off someone's mic, and grocery stores are allowed to remove flyers from their bulletin board. I totally agree with this. Obviously, a comedy club isn't a state actor but I don't understand why public access channels are being grouped in with grocery stores and comedy clubs.

Cory: Right. These channels were set aside as a government requirement. It's irrelevant whether a private company is managing those channels. That's just a convenience because we don't have state run media in the US. Public access channels were created as a public good. And to me that means they are state actors and they should not be limited by the regulations of whatever company happens to manage them.

Cameron: Americans are still free to express their opinions in a public space. But we should acknowledge that those free speech protections simply don't exist where it matters most. Today most of us get news or express our opinions through social media, but those spaces are all privately owned and without a federal mandate for First Amendment protections. The 2019 Supreme Court case signals a future that's mostly already here: free speech only extends as far as private corporations allow it.

Despite the fact that these platforms are overwhelmingly how the public and governments interact, their content is ultimately at the whims of their owners.

The takeaway here is not that social media is bad and shouldn't be trusted, it's that consumers and citizens of democracies must have higher expectations from the platforms we use. We have fewer free speech protections in the public forum than we did a generation ago, but it doesn't have to be that way.

We can democratize the forum again. And public access television should be our guide in how we produce, consume, and moderate our ideas.

Cory: Lost Threads is produced by two humans: Cameron Ezell, and myself, Cory Munson. If you're interested in watching the Great Satan At-Large, or Dirge for the Charlatans, we'll have links and sources for this episode on our website at lostthreads.org. If you liked today's episode and want to continue to support our work, please give us a follow on Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts. That's all from Lost Threads. Thanks for listening.